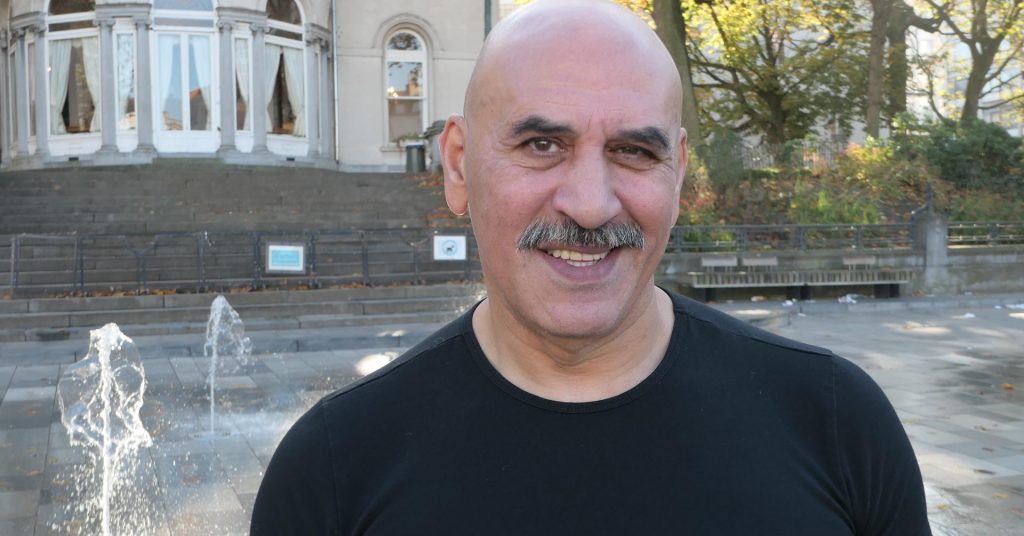

Bat Ye’or is an Egyptian-born British author and historian, who has focused on the history of religious minorities in the Muslim world and on the geopolitics of the European Union. She is known for introducing the West to the concept of dhimmitude, and forging the concept of Eurabia.

Bat Ye’or is an Egyptian-born British author and historian, who has focused on the history of religious minorities in the Muslim world and on the geopolitics of the European Union. She is known for introducing the West to the concept of dhimmitude, and forging the concept of Eurabia.

Grégoire Canlorbe: Could you start by reminding us of the motivations of the networks that orchestrate the EU’s migration policy and its anti-Israeli stance?

Bat Ye’or: The motivations of the networks in these two areas—the EU’s migration policy and anti-Zionism—are different but converge in their cumulative harmful effectiveness. This cumulative effect results from the deliberate policy of the Arab League and the Organization of Islamic Cooperation to link their relations with EU countries at every level to a European anti-Israeli policy.

The surrender of the European Community to these demands in November 1973, was obtained through the intolerable pressures of jihadist terrorism, particularly aircraft hijacking by the PLO in Europe, and the economic strangulation of Europe at the time through a severe Arab oil boycott. This linkage, however, is also part of the historical Christian tide that obstructed by all possible means—even through the genocide of Jews throughout Europe (1941-45)—the restoration of a Jewish state in its homeland. This current—allied with jihadism from the very beginning of Zionism[i] and in collaboration with the Muslim Brotherhood, particularly in the 1930s-40s and up to the present—can be seen by Europe’s support for the PLO, Hamas, Hezbollah, and all anti-Israeli forces.

The networks organizing the EU’s migration policy wrap themselves in a humanitarian ambiguity that conceals their financial sources. During the 1970-80 period of developing the EU’s Mediterranean policy, these motivations encompassed the entire range of Euro-Arab relations, as was officially stated later in the Barcelona Declaration (1994). Other declarations and dialogues among peoples, cultures, civilizations, and demographic hybridization—along with an important Muslim-Christian theological dialogue—aimed to create a homogeneous Euro-Arab strategic framework around the Mediterranean. This area—without Israel, if possible, and free from American influence—would supposedly gain from a strong Muslim immigration to Europe, and provide a civilizational and, above all, ethical source for the West, according to a globalist perspective of a Euro-Muslim hybridization, which would be created by a massive presence of Muslims in the West.

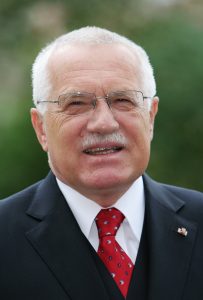

This perspective was, for example, articulated by Javier Solana, High Representative for the EU’s Common Foreign and Security Policy (1999-2009). In his presentation at Helsinki (Feb. 25, 2004) Solana declared, “Closer engagement with the Arab world must also be a priority for us. Without resolution of the Arab-Israeli conflict, there will be little chance of dealing with other problems in a region beset by economic stagnation and social unrest.” He then explained that future security would depend on a more effective multilateral system.[ii] Europe would become stronger in building a stronger United Nations, and in being firmly committed to effective multilateralism.

All these motivations were integrated into the soft jihad strategy in the West, and sponsored by the OCI.

Canlorbe: How does the Eurabia plan influence the EU’s foreign policy toward China and Russia?

Bat Ye’or: I cannot answer for China, but regarding Russia, it is clear that a fractured and weak Christianity has always been an easy prey to jihadist invasions. It must be noted that the collapse of those empires was due more to internal enemies connected to those outside the empire than to military battles. This was particularly the case with the Islamization of the Byzantine Empire, especially after the schism in 1054, which divided Christianity into two hostile entities, Western and Eastern.

In the Eurabian context, the hatred and delegitimization of Israel provide a spiritual and theological weapon for the European trends of Islamophilia and anti-Semitism to abandon Judeo-Christianity and rally to Islam. The current war aims to replace Israel with Palestine, an entity that has never had historical existence and a creature forged by Christian anti-Semitism from the 1970s[iii]. Palestine had a special connotation in early Christianity regarding Jews. The destruction of the ancient kingdom of Judea by the Roman army in 135 CE and its renaming as Palestine, was interpreted by Church theologians as a divine punishment against a supposedly deicidal people. The Christian prohibition to Jews to return or live in their homeland is rooted in this belief, as well as the traditional Christian anti-Jewish antagonism. As for the Muslims, the word and notion of Palestine is absent from the Quran; their war against Israel is based on the jihadi ideology which requires that Islamic law rule the planet. Islamic belief, however, destroys the historical foundations of Judaism and Christianity to replace them with the Islamic vision of biblical history, in which Islam preceded the other two religions. Palestinianism, the common Muslim-Christian fight against the Hebrew state, can only hasten the de-Christianization of the West. The case of Lebanese Christianity, destroyed by the PLO—an organization supported by Europe to eradicate Israel—is an illustration.

Canlorbe: Will the new Trump administration have a positive impact on issues such as the situation in Gaza and in Ukraine, in your opinion?

Bat Ye’or: I had high hopes that this administration would succeed in bringing peace to Europe, but too many forces and interests wish to weaken the European continent through the deterioration of the war in Ukraine, and I fear that we are heading in that direction.

As for Gaza, as long as Europe continues to collaborate with all the military-terrorist organizations that clearly display their extermination policy against the Jewish people, we will see no improvement. The first condition for a positive issue is to free the pseudo-Palestinian people from their eternal refugee status, imposed and instrumentalized against Israel by the EU as a weapon of destruction to replace the Jewish State. After all, the so-called Palestinians—mainly Arab and Muslims immigrants from the 19th century who had fled from Israel during the Arab 1948 war which they provoked hoping to exterminate the Jews—proclaim that they belong to the Arab Ummah [Muslim community]. Until the 1970s, they had campaigned under the banner of Arab nationalism with their leader, the Grand Mufti of Jerusalem Amin al-Husseini, Hitler’s admirer, ally and collaborator. Many could return to their homelands: to Jordan, Egypt, Iraq, and Syria. None of the sacred Arab and Muslim texts mentions a geographical location in the biblical Hebrew territories, nor any historical episode that would justify a connection with land in today’s Israel.

Europe could let them go to the 56 Muslim states or the 22 Arab countries, all of which were formed through the expulsion of millions of non-Muslim natives who, for their part, never benefited from any universal and providential aid like that provided by UNRWA. As a former refugee from Egypt striped of all possessions, I can attest to this, as do millions of Jewish and Christian refugees from Arab countries over the centuries, particularly after the failed 1948 Arab war of invasion against Israel. Europe never condemned the military invasions by five Arab States that seized and colonized Jewish lands according to both the Balfour and San Remo Declarations. There, their millenary old Jewish population were killed or expelled, their houses pillaged, their synagogues burned. Europe felt no need to provide help. It is true that just three years before, it was busy to deport Jews to the extermination camps spread over its territory. It was not prepared to help them against its former ally.

Canlorbe: In the Middle Ages, Rabbi Maimonides (who was appointed the head of the Jewish community in Egypt) saw Islam as rooted, albeit imperfectly, in Biblical teachings; and as intended—within the divine plan—to civilize the pagan Arabs and prepare them for the universal reign of the Torah in future messianic times.

Bat Ye’or: I share Maimonides’ opinion. One must understand the primitive and cruel living conditions of the inhabitants of Arabia before Muhammad to appreciate the value of the elements of humanity and spirituality brought by the Quran. The Arabs themselves, witnessing the example of the Jews and Christians in Arabia, hoped to obtain from Muhammad a similar religion. Muhammad responds to their request and tells them that he has brought them a religion in Arabic for Arabs. It is up to Muslims to undergo bringing their religion up to date, as other religions around the globe have done, to uphold values free from the prejudices of the past. As for messianic times, I would not even dare to imagine them.

Canlorbe: May the harmonious relationship between Israel and Sunni states raise hopes for the fulfillment of Maimonides’ hope?

Bat Ye’or: Perhaps… on the condition that they accept the people of Israel, their redemptive mission within humanity, their liberation from the ignominy into which the Christian accusation of deicide has confined them—a charge abrogated by Vatican II but still factually present in the Western refusal to recognize Jewish sovereignty in Judea, Samaria and Jerusalem. A second condition needs to be the abolition of the inhumane status of dhimmitude[iv], enshrined in the jihad ideology that aims at destroying all non-Muslim faith in order to impose the shariah laws over the planet. We are still far from this move … However, the definitive abrogation of dhimmitude, which would occur through the recognition of the legitimacy of the State of Israel in its historical homeland, is a principle that would benefit all of humanity and promote peace among everyone.

The tsunami wave of hatred against Israel and Jews that submerged the West since the 7/10/2023 embodies precisely this nazi-jihadism exuded by Christian-Muslim alliance against Zionism, so pregnant since the 1923 Lausanne Treaty. This Treaty legitimized a sovereign State for the Jewish people in their historic homeland with secure borders from Gaza to the Jordan River. Simultaneously, the same Treaty created on 70% of a Palestinian territory delineated for the first time since the Roman conquest (135 CE), the establishment of an Arab state for Muslims and Christians. Those decisions ratified by the League of Nations are endorsed by its successor, the UN and cannot be nullified. This modern anti-Israeli exterminatory wave is the prolongation of the Euro-Arab anti-Zionist Nazi alliance that produced from the 1920s the anti-Jewish hatred that generated the Shoah. It continues today, carried over by the Eurabian ideology. However as the European states support for murderous anti-Israeli jihadist ideology grows stronger, the more these states are destroyed by it. In Islam, Jews and Christians are cut from the same cloth. What is done to Jews is done to Christians as well and vice-versa as they have exactly the same legal statute. This is the great lesson given to us by the knowledge of dhimmitude and for this reason, forbidden. Yet we can see by our own eyes Europe collapsing under a self-injected poisonous Jewish-hating Eurabian venom.

[i] See Bat Ye’or, Le Dhimmi documents avec une étude de Rémi Brague, Les Provinciales, 2025, p.42.

[ii] Speech of Javier Solana at Helsinki, 2/25/2004, “The European Security Strategy—The Next Step?” in Cahier de Chaillot, Vol. V, n° 75, Sécurité et Défense de l’UE, Textes fondamentaux, 2004. Institut d’Etudes de Sécurité, Union européenne, February 2005, Paris.

[iii] In January 2004 in the course of an European investigation on EU misdirected funds by the Palestinian Authority, Javier Solana, the EU commissar for foreign policy and security, declared that Europe’s duty was to help the Palestinian Authority, adding, “If it didn’t exist we would have to invent it!”, in Le Temps, Geneva, February 4, 2004. See Bat Ye’or, Eurabia, The Euro-Arab Axis, 2005.

See also: “After a fixed deadline, a UN Security Council resolution should proclaim the adoption of the two-state solution. It would accept the Palestinian state as a full member of the UN and set a calendar for implementation. It would mandate the resolution of other remaining territorial disputes and legitimize the end of claims. If the parties are not able to stick to [the timetable], then a solution backed by the international community should be put on the table.” – EU Foreign Policy Chief Javier Solana, during a lecture in London, asserting that if Israel cannot arrive at a final-status agreement with the Palestinians, the UN should enforce its own. (Jerusalem Post, July 12, 2009)

[iv] Dhimmitude is the name given to the comprehensive political, social, juridical, religious Islamic system governing the non-Muslim populations that were defeated by the Jihad war. It has, therefore, its roots in the jihad ideology and military legal rules. From the 8th to the 12th century, as the Muslim jurisdiction developed, it integrated in the shariah jurisdiction built on Muslim sacred Scriptures the system of dhimmitude. A great number of Christian anti-Jewish laws from the fifth and six centuries were absorbed into dhimmitude. This common anti-Jewish ground led sometimes to a Christian-Muslim alliance for persecuting Jews in Muslim countries. In the 20th century, this trend achieved its peak in the Shoah and is now renascent after fifty years on anti-Israeli indoctrination.

That conversation was originally published on Gatestone Institute, in June 2025