Warning [December 2021]. Since many years, already, Grégoire Canlorbe is now totally retired from politics and no longer has any responsibility in any political party. As it stands, he has no affiliation to any political structure; and has no affiliation to any institute or ideological organization. His ideas also have much evolved since this article, which he doesn’t endorse anymore. Canlorbe used to be a sort of neoconservative with alt-right tendencies (as exemplified with this article); but he no longer has any alt-right tendencies nor any neoconservative tendencies.

As thorny as the issue of the Indo-European character—at a linguistic, genetic, or ideological level—of the Jewish ethnicity may be, Judaism has been decisive in edifying, and enriching, the Aryano-Christian civilization of the white race.[i] Indeed, there is little doubt that Indo-European peoples have indulged in the cultural appropriation of the sacred texts of Judaism; and that the Old Testament, its myths and its conceptions at large, has played a role in Christian Europe not less determining than the Greco-Roman heritage at large. There is also little doubt that the aristocratic-warlike ethos (which intends to design society for the benefit of aristocrats searching for individual fulfillment, and individual recognition, through their military exploits) is not only common to all Indo-European peoples, but besides, characterizes the Old Testament and the other sacred texts of Judaism.

An example between thousands of the happy marriage between the Indo-European Weltanschauung and Judaism is that of the coronation of the kings of France, the French royalty honoring David and Solomon and seeing itself as the continuation of the kingdom of Judah: this is how the hyacinth of the mantle worn during the coronation evokes the garment of the high priest of Israel (which represents not only the nation but the universe taken as a whole); and how the future king, during the ceremony, is given a ring that symbolizes the Catholic faith, but also a scepter and a hand of justice that refers to David. Concerning the celestial mantle, various kings and emperors were using it since the Ottonians: let us mention in particular that of Henry II, preserved in Bamberg and covered with embroideries which describe situations of the Bible and celestial constellations. Recognizing himself in the music-loving character of David, Louis XIV had the painting of David playing the harp (painted by Domenico Zampieri) installed in his apartments.

[Read more…] about Why French nationalism should embrace Judeophilia and Zionism

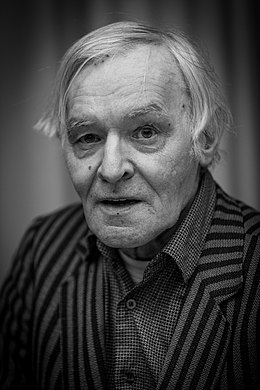

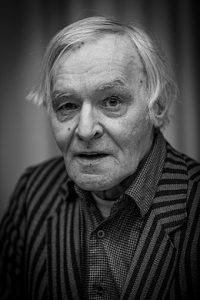

Guillaume Faye is a French philosopher, known for his pro-Zionism right-wing paganism, his call for a Eurosiberian Federation of white ethno-states, or his concept of archeofuturism, which involves combining traditionalist spirituality and concepts of sovereignty with the latest advances in science and technology.

Guillaume Faye is a French philosopher, known for his pro-Zionism right-wing paganism, his call for a Eurosiberian Federation of white ethno-states, or his concept of archeofuturism, which involves combining traditionalist spirituality and concepts of sovereignty with the latest advances in science and technology.