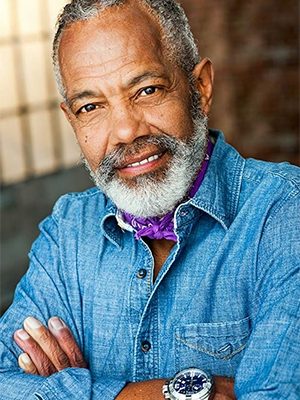

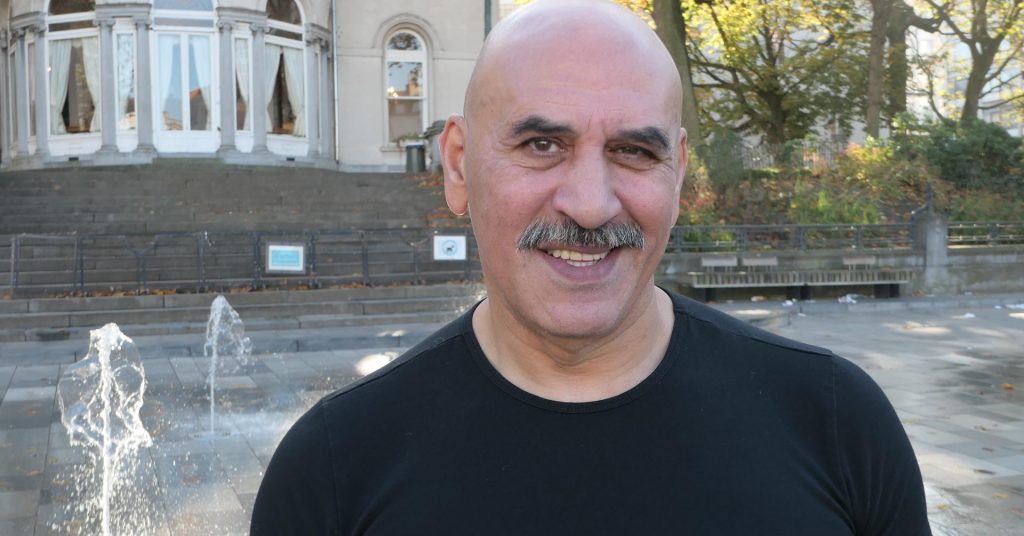

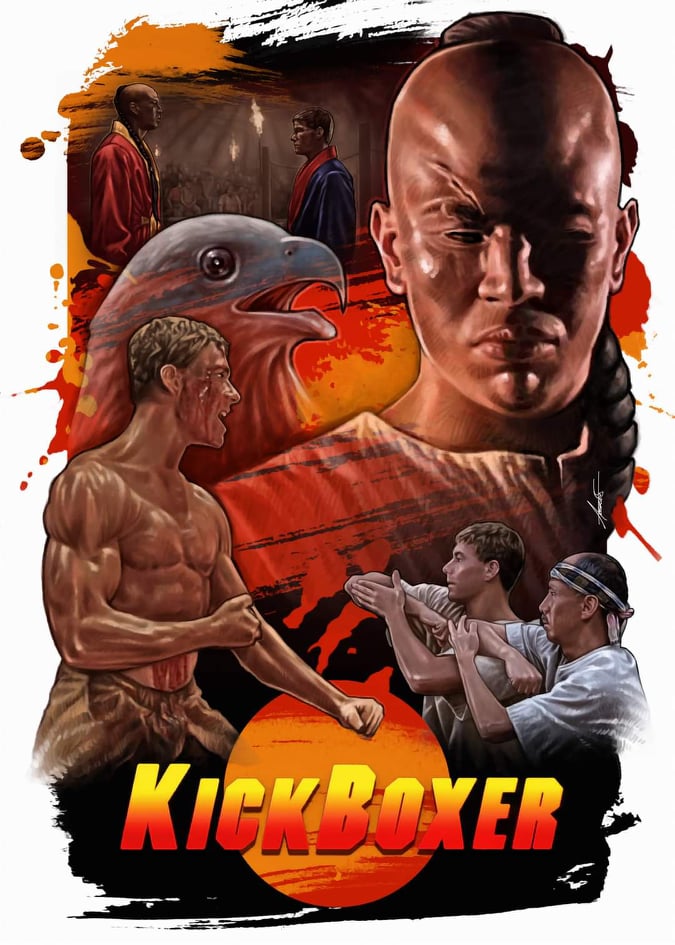

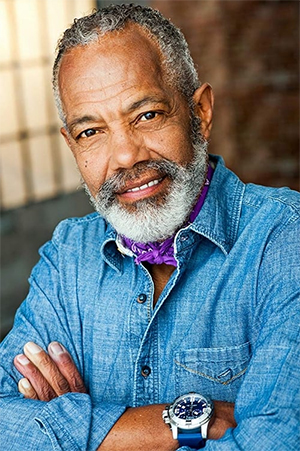

Haskell Vaughn Anderson III is an American film, television and theater actor. He is notably known for his role in the 1989 martial arts film Kickboxer—and his role in the 1976 film Brotherhood of Death.

Grégoire Canlorbe: You served as president of Catholics in Media for two years. How did Jesus enter your life?

Haskell Vaughn Anderson III: I was always educated in Catholic schools. I’m a practicing Catholic. It didn’t do anything for me career-wise, but it was an enjoyable experience. It gave me the opportunity to become a member of the Jewish committee, which is a committee that goes to different film festivals. And I was at the Venice Film Festival in 2005. That was the year that Broke Back Mountain came out and a few other films. Yeah, it has touched me in a professional way. Yes, it did. I can’t say it hasn’t. And it was an enjoyable experience here, in Los Angeles. I started off as a regular member of Catholics in Media then, I was vice-president for two or three years and president for two.

Grégoire Canlorbe: When it comes to those moviemakers (such as Martin Scorsese, Abdel Ferrara, or Mel Gibson) whose work and mindset, at least at a cultural level, are especially Catholicism-framed, which of them comes as your favorite?

Haskell Vaughn Anderson III: I don’t know how they actually practice Catholicism. I do know that Mel Gibson is more of a strict Catholic, so to speak. Got that from his father, from what I’ve been told. We never spoke about it, although we have been in person together, but we never spoke about the church or his practicing of his faith. So, I don’t know how devout he is. But his church is in Malibu, somewhere, that his father built. I have not been there.

Grégoire Canlorbe: Please tell us about 40 Days Road and your other ongoing movie-projects.

Haskell Vaughn Anderson III: 40 Days Road. Yes. We’re still in development on that project. It’s not on the back burner. We’re just holding off on it for a little bit because we’re involved with another project that I was involved with more than 30 years ago as a stage production. We are now developing it. The script has been written. We’re now looking for investors. We will be at the American Film Festival, this coming November, pushing it. It’s actually a play that was written by a friend of mine who was in another play with me called Traces About Vietnam. He wrote the play, and it won what they call the 6th NAACP Image Award. One of them was the best supporting actor, which I was honored to win. We are hoping that we will have production of that film. Is that 40 Days Road? No, I’m sorry. This film is called Detroit Rounds. The play was actually called Rounds. We’re calling it Detroit Rounds because we’re going to set it in Detroit. This is a movie, and the play was about four guys who worked in the same plant together. They’re having this kind of civil war thing within the company because the union wants to send jobs overseas and cut employment of these guys. This is their life, so it reflects what was going on here in the auto industry in Detroit in this country back in the, I would say, 70s, after Vietnam. They lost a friend, so they get together one night to celebrate the death of this friend that they lost and to watch the championship fight between Muhammad Ali and I forget who the other character, the fighter, was, but we will see that when the film comes out.

40 Days Road, that’s a film about a cardinal. It was an idea that I cooked up and spoke to my writer friend who is now one of my partners in our film company. It’s about a cardinal who has come to a point in his life where he’s somewhat confused about where he’s going and what it is that he’s supposed to be doing. Even though he has attained that rank of cardinal, he still has some thoughts in his head. It’s an interesting story. It all takes place in Sudan. Before he became a priest, he was a medical physician, and so, he actually has two occupations. He goes off to Darfur to see a friend that he had met while he was in the Jesuit seminary. He actually ends up meeting a woman who was also a physician. There’s much trial and tribulation to that story.

Grégoire Canlorbe: The arc story for Winston Taylor, your character in Kickboxer, who, haunted by the souvenir of his failure to save a friend in Vietnam, ends up redeeming himself through helping Kurt Sloane [Jean-Claude Van Damme] defeat Tong Po [Mohammed Qissi] and the mafia, is quite moving. How did you put yourself so convincingly in Taylor’s shoes?

Haskell Vaughn Anderson III: Well, part of acting. I guess I made myself that character. I became Winston Taylor, and I felt from talking to other people with what their experiences were during that period of time, and I just used them.

Grégoire Canlorbe: Do you feel the character’s fate should have been further explored in another Kickboxer installment or spinoff?

Haskell Vaughn Anderson III: I don’t know. Perhaps, it would have been feasible. It probably could have worked, but they chose not to do it. I didn’t ask, but I had thought about what that would have been like. How far had the character advanced? What was his story afterwards? It would have been interesting. But they didn’t do it, but that’s okay.

Grégoire Canlorbe: Despite the movie’s somewhat low budget, the short gunfight at the end of Kickboxer, when Winston Taylor [Haskell V. Anderson III] comes to rescue Eric Sloane [Dennis Alexio], is pretty good. How do you account for such effectiveness on the movie’s team’s part?

Haskell Vaughn Anderson III: Actually, I guess I never really thought about it that way. The character had something to do, he had to rescue a friend, Jean-Claude’s brother, Kurt’s brother. And being that he was a military vet, he had access to what he needed to get the job done. It was interesting. Actually, that was my first day of shooting. It was very interesting. We shot that part in Hong Kong. It was not a difficult scene. Actually, I’m not gonna say it was easy, but it took a little bit of time to work into it on that day. Although I has been rehearsing the lines for some time. But to get that emotional feel on that day, it took a few minutes in the trailer to get myself ready.

Grégoire Canlorbe: Did you stay in touch with Jean-Claude Van Damme or other actors in Kickboxer?

Haskell Vaughn Anderson III: Other actors, yes. The director, David Worth. Michel Qissi, I see every now and then, I think we were together about, I think, at least, two years ago. Jean-Claude, rare, very rare even though we used to live a block away from each other. And Rochelle Ashana… we do emails through Facebook pretty often. She sends photographs. She has a son that’s going to UCLA. I bet he’s in his senior year. He’s either a junior or a senior. She’s supposed to be visiting from Hawaii very soon. I’m waiting to hear from her because we haven’t been together in quite some time.

Grégoire Canlorbe: How do you assess the evolution of Van Damme’s career since Kickboxer?

Haskell Vaughn Anderson III: It’s interesting. Here you have an action star, so to speak, who actually got to the top of the pyramid and just, I guess, in some way, just lost it. But it’s an interesting article that was in the New York Times just the other day. Someone is doing an off-Broadway or off-off-Broadway production of Jean-Claude Van Damme: The Rise and Fall, of Jean-Claude. It’s an interesting review. I think it got enough attention that it got reviewed by the New York Times. And they thought was pretty good.

Grégoire Canlorbe: Quentin Tarantino is openly a huge admirer of Brotherhood of Death. Have you ever met him? Did you enjoy his last movie, Once upon a time in Hollywood?

Haskell Vaughn Anderson III: No, I have not met him. I didn’t see the whole film. I have it, but I haven’t really watched the entire film. I do that sometimes. I read a lot of books, sometimes I don’t finish them.

Grégoire Canlorbe: When it comes to characters in classical theatre (Hamlet in Shakespeare, Don Rodrigue aka Le Cid in Corneille, Theseus in Racine, Don Juan in Tirso de Molina, etc.), which are those of them you especially aspire to play?

Haskell Vaughn Anderson III: I started my entire career in theater. Done Shakespeare. I’ve never done Hamlet, but I did Richard III, Comedy of Errors. God! can’t even remember the names. I don’t have my resume in front of me to tell you where the plays were. But it was a very rewarding experience, doing Shakespeare all the time. Othello. I didn’t play Othello, but I was one of the major characters. Was it Lodovico? Yeah, I think it was Lodovico. It was just such a discipline, a base. That’s what I like about British theater. The actors learn the classics. I think you need to do that. That’s my opinion.

Grégoire Canlorbe: Those many-hundred-years-old classics of theater are enjoying tenacious fame; but very few of the movies that are successful when released meet a fame that is other than ephemeral. Very few are not forgotten more or less rapidly.

Haskell Vaughn Anderson III: That is so true. Very few from all the films that have been done. Very few do you remember. It’s just amazing. Film comes down today, it’s forgotten next month. All of a sudden, you see it on the cable, and then it’s forgotten a week later.

Grégoire Canlorbe: Screenwriters could learn a lot from Shakespeare, Euripides, Aeschylus, and Sophocles. Screenplays would be much better.

Haskell Vaughn Anderson III: It’s difficult. Difficult in the sense that it takes a lot time to do a really, really, really good screenplay. But if people weren’t so much interested in just making a lot of money, just throwing anything out there, I think screenplays on a whole would be a lot better. But that’s business.

Grégoire Canlorbe: Please tell us about your long-established collaboration with playwright Vince Melocchi.

Haskell Vaughn Anderson III: Vince Melocchi belonged to the same theater company I am still a member of. And Vince is, too, even though he moved back East. I did two of his major productions. One of them went to off-broadway, which was just a wonderful experience! Julia was the name of this play. Before that, we did a play called Lions about a group of people who were Detroit Lions football fans, and they had this club that they went to and spent a lot of time at. It was very, very, very beautifully written. I really enjoyed those characters that I portrayed. We were members, I would say, since 1994. It was at the at Pacific Resident Theater in Los Angeles, here, and still active, and it’s getting more active now since we are getting beyond the epidemic. Vince is still writing. We’ll see what he comes up with next. But a he’s an excellent writer.

Grégoire Canlorbe: Thank you so much for your time. Is there anything you would like to add?

Haskell Vaughn Anderson III: We’re talking about a film, Kickboxer, that was made 30 years ago. It’s just unbelievable how much of a following it has! You’re walking down the street, and somebody’s shouting out your line. “Oh, you in that film Kickboxer, can we have a picture?” I had no idea the film would be attracting that much attention this long. None, whatsoever. You can call it. What do they call it? A cult film. But Quentin Tarantino he was a fan of another film, Brotherhood of Death. Actually, it was my first film. You can see that on YouTube. That has picked up a following of its own, also. I used to run from that film. Oh, my God, please don’t share it! But, hey, you did it. You own it. Be proud of it.

If people see this interview and they enjoy it and they’re thinking about acting or directing or writing, just be patient, just do it and be disciplined, discipline yourself. This is what I want to do and I want to be the best of the best. But I hope I satisfied you.

That conversation was originally published on Bulletproof Action in February 2023