Philippe Fabry is a lawyer and a theorist of history. His approach, which he calls “historionomy,” endeavors to identify the cyclical patterns of history. He authored Rome, from Libertarianism to Socialism, A History of the Coming Century, and The Structure of History. His website is: https://www.historionomie.net/.

Philippe Fabry is a lawyer and a theorist of history. His approach, which he calls “historionomy,” endeavors to identify the cyclical patterns of history. He authored Rome, from Libertarianism to Socialism, A History of the Coming Century, and The Structure of History. His website is: https://www.historionomie.net/.

Grégoire Canlorbe: You do not hesitate to challenge the usual discourse (which liberals [libertarians, classical-liberals, anarcho-capitalists, free-marketists] do not avoid, even for the most conservative of them) claiming France to be an artificial construction from the building and unifying State: a political work whose plinth is no more geography than ethnicity or blood. Far from having formed differently from other European nations, France has, according to you, been built around an ethnic and territorial reality; and globally follows the same trajectory in its history. Could you come back to that subject?

Philippe Fabry: Yes, it is indeed a common place in the commentary on the history of France to say that it is the State which made the Nation, while among our neighbors it would be the Nation which made the State. I can’t say if historians believe it, because it’s just not the kind of question they ask themselves these days, but it’s the kind of ready-made thinking that is prized by journalists and politicians who pride themselves on diagnosing “French trouble.” But in truth that dichotomy opposing France to the rest of Europe, if not the world, is fallacious, in two respects: first, all Nation-States are constituted according to a standard model (in reality two, but France is in the most frequent, I will come back to it), then the State does not have a more determining role there than the territorial and ethnic factors.

There are two models of the appearance of Nation-States: the most common model, the most immediate, primary one, is that of the long-term gathering—around six centuries—of territories and people under one single state authority. The other model is the one that I would say “secondary” of the Nation-States born by secession, during an independence revolution: that is the case of Rome vis-à-vis the Etruscans, the separated United Provinces formerly Spanish possessions, the United States of America; those are formed when a population geographically and culturally too much distant from the state base of a “primary” Nation-State is under its control for various reasons.

France belongs, like all major European States, to the first category. The model is as follows: in a populated territorial area, ethnically and linguistically relatively homogeneous, but where there is no State, either because none has ever emerged—for example Germania of the early Middle Ages—, or because it is a former imperial state which has withdrawn—that is the case of Gaul at the same period or of Great Britain after the ebb of the Danes in the X century—, the primitive regime is feudalism and therefore extreme political fragmentation. In the absence of a large-scale exogenous event, generally the invasion by an imperial power, a feudal lord more powerful than the others appears over time, who is logically the one who reigns over the economic lung of the territorial area. That economic lung, a fertile agricultural region, is very easily identified by looking at a relief map: it is a large plain, the largest in the territorial area: the Paris basin in France, the North German plain for Germany, the Guadalquivir plain for Spain, the London basin for Great Britain. The seigniorial power which can rely on this economic lung has a decisive advantage in resources and can extend over all the space which is naturally peripheral to it, that is to say both culturally close, and belonging to a geographically well-defined territorial area: the whole of Gaul for the Paris basin, including the Breton peninsula, the Massif Central and the smaller plains of Aquitaine and Languedoc; the entire island of Great Britain for the London basin, winning over Cornwall, the mountainous Wales and Scotland; all of southern Germany for the northern plain, including mountainous Bavaria. Of course, those centers of power do not stop at sharp boundaries, which for centuries engenders conflicts over the exact boundaries of the areas of influence. Those conflict zones are generally characterized by a hybrid character allowing them to be linked to several groups: an ethnic aspect could make Britain be disputed to France by England, language linked Alsace to Germany while the largest geographic proximity to the Paris basin made it lean towards France, and so on. It is rare that a border so clear separates two territorial areas that it is never challenged, but we can say that this was the case of the Pyrenees between France and Spain—although Roussillon, close to culture Catalan, did not become French until the XVII century.

That dominant seigniorial power then builds the state, first by going beyond the feudal system by creating an assembly representative of the orders: urban bourgeoisie, nobility, clergy, to which the peasantry is added in the Nordic countries. That assembly allows the dominant seigniorial power to give itself a higher stature than that of the rest of the nobility and to embody the first national representation. That new paradigm leads to the construction of an administration exercising, more and more uniformly throughout the controlled territory, the regalian functions. The population gathered under the same authority gradually becomes a political community, becomes culturally uniform, and develops a national feeling. And it is when that national feeling is sufficiently present, and when happens an event—a lost war which discredits that regime which is called “administrative monarchy”—, that what I call a movement of national revolution occurs, which is the final stage in the constitution of a Nation-State by making the Nation the true holder of sovereignty, and therefore of the power of the State, through a parliamentary regime. That revolutionary movement lasts about forty years and goes through various systematic stages: collapse of the regime, radicalization of the revolutionary phenomenon, military dictatorship, partial restoration of the old regime, and final parliamentary change.

So it’s always a bit the State that makes the Nation, but at the same time the Nation that arouses the State. The geographic expansion of the State is constrained by cultural, demographic, linguistic and obviously purely geographic factors, but its emergence and consolidation are themselves the product of an ethno-geographic reality. It is a kind of feedback loop, and it is rare that a State absolutely corresponds to its natural ethnico-geographical zone: the competition of large States creates disputed zones which are often resolved either through an arbitrary delimitation, or through fragmentation and the appearance of multi-ethnic, multicultural, plurilingual buffer States like Belgium or Switzerland—which may end up developing their own identity, certainly, but one more accidental.

The determinism is not absolute and leaves the possibility of several combinations, but it is clear that it is the most “obvious” one which generally triumphs. Thus in France, two nations could have been born, because there are two basins: the Parisian and the Aquitaine. For a long time Bordeaux was the capital of that Aquitaine basin and Aquitaine dominated the country of Oc, while the country of Oïl depended more naturally on Paris. The distinction between the two countries could have endured, since each had a certain linguistic and cultural unity: the language of Oc against the language of Oïl, a country of written law against a country of customary law. But on the one hand the Parisian basin is much larger than the Bordeaux basin, and on the other hand the “natural” territorial area was rather on the scale of the whole of the former territory of Gaul, whose settlement base had besides remained the same as during Antiquity, the Great Migrations having not constituted a real demographic break. The Paris basin therefore succeeded in its vocation to dominate the whole which has given France.

Another example: Germany saw the development of two centers capable of unifying the German nation: Austria and Prussia. Prussia controlled the plain of North Germany, and Austria dominated the plain of Pannonia (Hungary). That resulted into a division of the Germanic space between the two centers until the Great War, and ultimately the impossibility of keeping them lastingly unified after the failure of the Third Reich—even while the Germany of the seven electors appointed by the Golden Bull in 1356 covered all of those German-speaking territories.

I think that the political debate would often gain if those invariants of the state and national construction are better known, because they say a lot about what can or cannot be a Nation-State, about the deleterious effects that can have on a Nation-State a constituted mass immigration, for example.

And as for liberals [libertarians, from classical-liberals to anarcho-capitalists] there is a remark that I like to make to them, and that they generally take badly, it is that if the Nation-State is built in such a systematic way, it is because it is the most efficient product on the public security market, so that if we were to recreate an anarchic society, in the long term it would be towards the re-emergence of Nation-States that the political and social order would tend.

Grégoire Canlorbe: While Greco-Roman paganism—on that point, in phase with Judaism—breaks with the veneration of motherly Nature, the pre-Indo-European gynecocratic spirit, the biblical conception of time as linear (and of cosmic and human history as endowed with a beginning, an end, and a progression) contrasts with the pagan motif of the eternal return of the same. You assert both your Catholic heritage and your cyclical conception of history. How is that duality conciliated within your intellectual life?

Philippe Fabry: It always seemed natural to me, faced with that kind of conceptual opposition, to think that the truth was more likely to be a mixture of the two. Cyclicity and linearity are not necessarily contradictory if we consider that there are several scales to consider, several temporalities. And it seems obvious to me that history is both cyclical and linear. And that is not proper to human history, but also to natural history. Take the evolution of species: it is linear, there is no turning back, but it is based on a cyclical phenomenon which is the life of living individuals: their conception, their birth, their maturation, their reproduction, their death. It is through that recurrence that nature, through mutations which are then selected naturally, makes species evolve. The same goes for humanity: it is subject to certain recurrences, but those recurrences end up drawing a linear pattern and a general progression: in the demographic mass of the species, the size of its political communities, its scientific and technical power, its artistic sophistication. Its destiny is linear, but its embodiment is recursive. Which led me to suggest, and my work always leads me further in that direction, that human history can be modeled in the mathematical form of a cellular automaton, which is also a tool for modeling the appearance and development of life.

[Read more…] about A conversation with Philippe Fabry, for The Postil Magazine

Kamel Krifa is an actor, film producer, and Hollywood’s stars trainer—including Jean-Claude Van Damme, Michelle Rodriguez, Eddie Griffin, Steven Seagal, and many other ones. Krifa ranks among Van Damme’s longstanding collaborators and personal friends, acting alongside him in various movies. This conversation with cultural journalist Grégoire Canlorbe first happened in Paris, in July 2017; it was resumed and validated in April 2020.

Kamel Krifa is an actor, film producer, and Hollywood’s stars trainer—including Jean-Claude Van Damme, Michelle Rodriguez, Eddie Griffin, Steven Seagal, and many other ones. Krifa ranks among Van Damme’s longstanding collaborators and personal friends, acting alongside him in various movies. This conversation with cultural journalist Grégoire Canlorbe first happened in Paris, in July 2017; it was resumed and validated in April 2020.

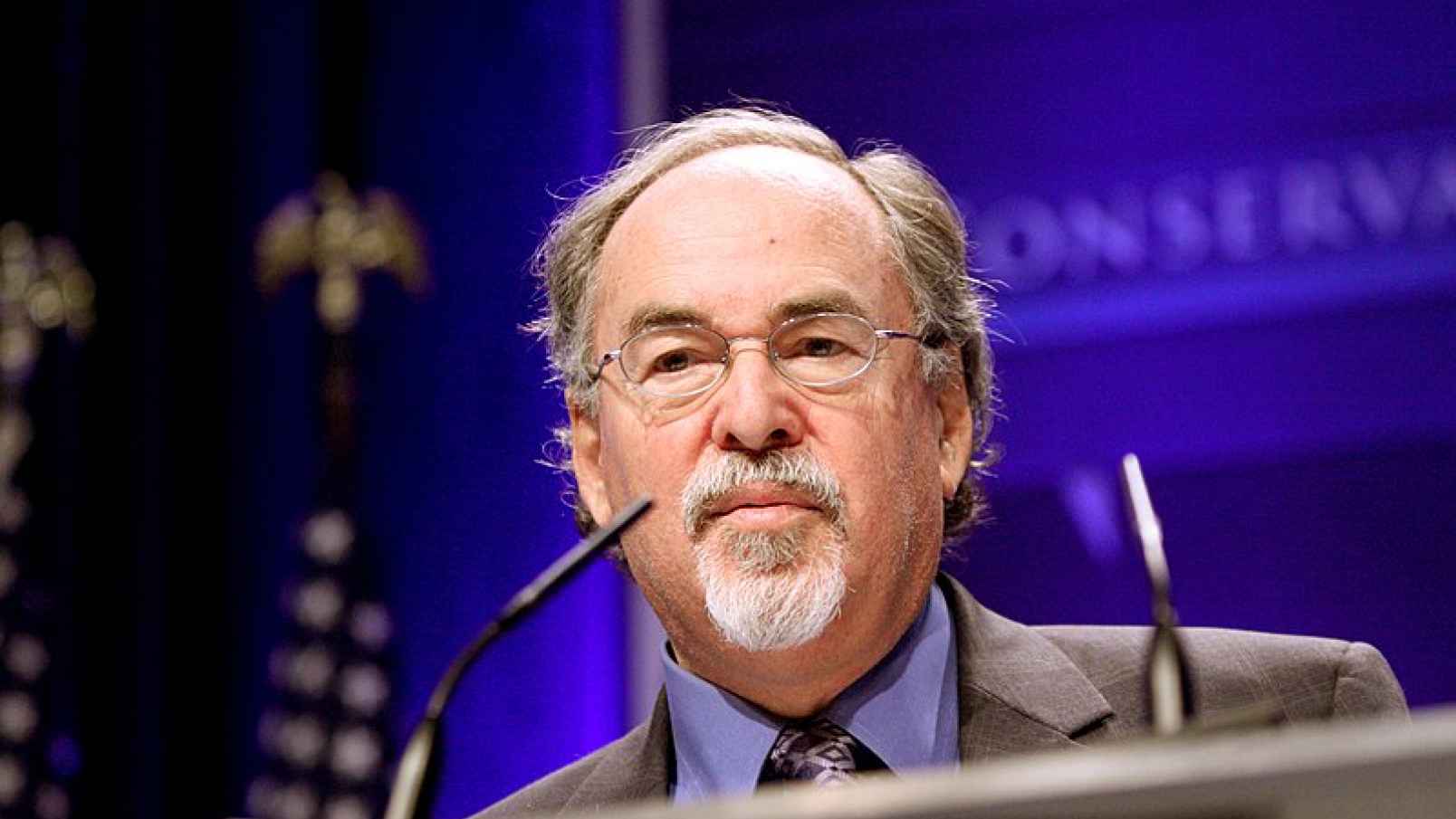

David Joel Horowitz is an American writer. He is a founder and president of the think tank the David Horowitz Freedom Center (DHFC); editor of the Center’s publication, FrontPage Magazine; and director of Discover the Networks, a website that tracks individuals and groups on the political left. Horowitz also founded the organization Students for Academic Freedom.

David Joel Horowitz is an American writer. He is a founder and president of the think tank the David Horowitz Freedom Center (DHFC); editor of the Center’s publication, FrontPage Magazine; and director of Discover the Networks, a website that tracks individuals and groups on the political left. Horowitz also founded the organization Students for Academic Freedom.

Michael H. Hart is an American astrophysicist, historian, and white separatist militant. He is mostly known for the Fermi-Hart Paradox, and his books The 100: A Ranking of the Most Influential Persons in History and Understanding Human History. He was a

Michael H. Hart is an American astrophysicist, historian, and white separatist militant. He is mostly known for the Fermi-Hart Paradox, and his books The 100: A Ranking of the Most Influential Persons in History and Understanding Human History. He was a

Guillaume Faye is a French philosopher, known for his pro-Zionism right-wing paganism, his call for a Eurosiberian Federation of white ethno-states, or his concept of archeofuturism, which involves combining traditionalist spirituality and concepts of sovereignty with the latest advances in science and technology.

Guillaume Faye is a French philosopher, known for his pro-Zionism right-wing paganism, his call for a Eurosiberian Federation of white ethno-states, or his concept of archeofuturism, which involves combining traditionalist spirituality and concepts of sovereignty with the latest advances in science and technology.

Majid Oukacha is a young French essayist who was born and grew up in a France which he recognizes less every year. « A former Muslim but an eternal patriot, » as he sometimes likes to describe himself, he is the author of

Majid Oukacha is a young French essayist who was born and grew up in a France which he recognizes less every year. « A former Muslim but an eternal patriot, » as he sometimes likes to describe himself, he is the author of