Kenya Kura is currently an associate professor at Gifu Shotoku Gakuen University in Gifu prefecture, Japan. He graduated from the University of Tokyo (B.A. in Law) and obtained Ph.D. in Economics from University of California, San Diego in 1995. His original papers regarding the following conversation are “Why Do Northeast Asians Win So Few Nobel Prizes?” (https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.2466/04.17.CP.4.15) and “Japanese north–south gradient in IQ predicts differences in stature, skin color, income, and homicide rate” (https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0160289613000949).

Grégoire Canlorbe: Could you start by reminding us of your main findings about IQ differences?

Kenya Kura: My first motivation about IQ study, basically, came from the simple fact that some IQ researchers, way back, like Richard Lynn and Arthur Jensen among others, reported that East Asians are higher in their IQ. And I was just wondering if it was true or not, and then, I went into the field of whether or not there is some kind of gradient of intelligence among Japanese prefectures. And so far, what I have found is very much in line with other findings that the Northern Japanese are somewhat more intelligent than the Southern residents on these islands. About the gradient amount Japanese people, what I have found is not at all unique: in Northern Japan IQ tends to be probably about three points higher than the average Japanese. And in the Southern Island of Okinawa, for example, it is like seven points lower than the average. And pretty much, it varies. Sort of stylized pattern that I figured out for many times and very consistently. That’s pretty much it. Also, I’ve been probably more interested in the psychological differences between the East Asians and the Europeans than most of the European Psychologists.

Grégoire Canlorbe: Do you have something to say about the dysgenic patterns (i.e., the factors of genetic decline at the level of things like fertility gaps) in contemporary Japan—compared with the West?

Kenya Kura: Actually, Richard Lynn has been asking me for probably more than a decade, probably 15 years or so, if I can get some kind of evidence about this genetic effect in Japan. But unfortunately, I haven’t got a very solid dataset on the negative correlations—the so-called the famous dysgenic trend found almost everywhere in the world that more intelligent women tend to have fewer children. But, having said that, it’s very, very obvious that in Japan, this genetic effect is going on as much as in Western society. For example, Tokyo has the lowest fertility rate. And where most intelligent men and women tend to migrate when they are going to college or when they get a job and stuff like that. So, it’s apparent that most intelligent people are gathering in the biggest city areas like Tokyo, and Tokyo has the lowest fertility rate. So, it gives us some kind of evidence but, unfortunately, this is not a really solid analysis. I also figured out that the more educated you are, the fewer children you have. This is a very much stylized or prominent sort of phenomenon also found in Japan. So, I’m sure of this genetic effect.

Grégoire Canlorbe: Is it true that the taboo about genetic differences in intelligence is far less prevalent in Japan (and the other East-Asian countries) as it is in the West?

Kenya Kura: I have been working on this subject matter for at least 20 years, and I got the impression that the real taboo of this kind of research is pretty much the same as in Western society. But there is one very big difference: in Western culture you can always pursue your scientific theme or scientific field and prove you are right. And it’s a very Western idea: individuals have a right to speak up and try to prove they are right, but Asian culture doesn’t have that. So, the problem is that Japanese scholars are scholars in some sense, including myself, but, actually, most of them are just mimicking or repeating what Western people are doing. So, there aren’t many people actually trying to show or present their own thesis, their own theory, so to speak. So in that sense, if Western society or Western Science Society says A is right, B is wrong, in the Japanese society, it is pretty much subordinate to the whole attitude.

So, I would say that mainstream Japanese scholars tend to just follow the mainstream Western culture. Personally, as for this sensitive scientific field, I really don’t have any friend working on this matter. People, including myself, are afraid to be regarded as a very strange, cranky person who is saying: “look, in group data, we are so different that there isn’t much we can do to, for example, alleviate poverty in the third world or in developing countries.” If you say that, then people think, “What?” Even though you might be right—many people think you might be right—but it is not part of our culture to speak up, that’s why I don’t expect anything to come out of the Asian scientific society to have an influence on the Western science society.

Grégoire Canlorbe: While any evolutionary psychologist agrees, in principle, that human individuals are not tabula rasa genetically, most of them nonetheless refuse to admit that it applies to groups as well, i.e., that human groups exhibit as much specific genetic characteristics as do human individuals. In other words, all agree that a human individual (whoever he is) is endowed with a specific individual genome that contributes to shaping his psychological identity; but only a minority agrees that a human society (whatever it is) is also endowed with a specific collective genome that contributes to shaping its cultural identity. How do you account for that duality?

Kenya Kura: For this sort of question, I have pretty much the same opinion as other IQ researchers of this kind. Basically, as you said, many people agree about the genetic differences between individuals whereas, when it comes to group differences, they try to negate the existence of genetic differences. So, yes, there is a dichotomy, here. But I understand this idea because their point of view—because everybody wants to be a nice person. Right? So, if you are seeking for truth only as a scientist, that is fine. But we are not some sort of abstract existence without any physical reality because everybody around you feels awkward probably if you say: yeah, but, you know, group difference makes a lot of sense. And most of the sort of talk that inequality existing in this world is probably explained by genetic differences, as Richard Lynn and Tatu Vanhanen said, makes all the people around you feel very, very awkward or strange about your political sort of personality or your political view, itself. I can say only probably this much. So, many people are just politically persuaded not to mention—not only that—not to recognize, trying to make a lot of effort not to recognize the difference and try to negate the fact. That’s my understanding.

Grégoire Canlorbe: It seems the Indo-European cultural pattern that is the tripartite hierarchy of society for the benefit of a warlike, sacerdotal aristocracy with a heroic ethos (i.e., the ethos of self-singularizing and self-immortalizing oneself through military exploits accomplished in contempt for material subsistence) has been present or paralleled in traditional Japan. Do you suspect an Indo-European influence in Japan?

Kenya Kura: Oh, I have sort of an idea. It’s not very much proven, but Japanese society or Japanese people are basically a hybrid, about 30 percent of the original so-called Jomons before the Chinese or Koreans came, about two thousand years ago. And this Korean or, I would say, Chinese genetic factor constitutes about 70 percent. So 70 percent of Chinese plus 30 percent of indigenous Japanese people is the basic genetic mix of current Japanese people. And this kind of huge 70 percent explains the East Asian characteristics. Basically, it gives us looks like mine, right? Probably, any European can notice that Japanese, Korean, Chinese typically have different face characteristics. And although, as I said, Japanese people have 70 percent of retaining this genetic tendency, the 30 percent remains in our genetic structure. And I suspect that this natural 30 percent gives us more of a war prone personality than the Chinese or the Koreans. So, that’s why we put a lot of war emphasis, like the Samurais’ theory, as you might know: more martial arts, real battle and war, and really domination, all over Japan. That’s my understanding.

Grégoire Canlorbe: The traditional Japanese have been highly creative and sophisticated in the martial-arts field—to the point of surpassing the Westerners from that angle. Yet only the traditional Westerners have come to transpose to the field of science the art of fighting, i.e., to transpose to science the spirit of competition, innovation, and assertiveness associated with physical combat. How do you make sense of it?

Kenya Kura: It’s a very good point—an interesting point for me, too. My understanding about it is that, for example, French people seem to like judo a lot. I have heard that it’s very popular. So, for example, judo, or we have a similar sort of art that is huge called kendo. But that kind of martial art, as you said, has been very sophisticated in this country, and also in China, to some degree, maybe even more so. But that gives me an idea of science itself because science itself is equally into any kind of sort of natural—not only natural reality, but also the analytical view for every kind of phenomenon. So, for example, we don’t have social science, and we just import it from the West. It’s the same. I mean, natural science was imported from the West. And when it comes to science, it’s also based on logic—a heavy dose of logic and mathematics, usually. None of the Asians were interested in mathematics, at least not as much as Western people had been. So, when it comes, for example, to geometry, even the ancient Greeks were very much interested in it. The Chinese people never developed the equivalent of that kind of logic. And it’s also true that mathematics has been developed almost exclusively in Northern Europe within the last five hundred years. And Chinese people, although they were in higher numbers than White Europeans, they didn’t develop anything. Neither did the Japanese or the Koreans.

So, the problem is that East Asians tend to neglect the importance of logic. They don’t see that much. They just talk more emotionally, trying to sympathize with each other, and probably about political rubbish, more than Western people, but they don’t discuss things logically, nor try to express their understanding and make experiments to determine if something is true or not. Scientific inquiry is very much unique to Europeans. That’s my understanding. So, although it seems like East Asians are very quick to learn things—the Chinese are probably the quickest to learn anything—but they’ve never created anything. That’s my idea. So, they don’t have the scientific mentality, a sort of inquiry or sufficient curiosity to make science out of sophisticated martial arts.

It may be true that the “traditional Japanese have been highly creative and sophisticated in the martial-arts field—to the point of surpassing the Westerners from that angle.” But I guess nowadays even judo or any kind of martial arts is more developed or more sophisticated, a lot more sophisticated, in European countries. The Japanese or Chinese created the original martial arts. But their emphasis—especially the Japanese, they put too much emphasis on their psychic rather than physical power. So, when you look at any kind of manga or anime, the theme is always the same: the rather small and weak main character has got some kind of psychic power and a special skill to beat up the bigger and stronger enemy. And it’s pretty much like “the force” in the Star Wars movies. But in the case of Japan, it’s a lot more emphasized. So, they tend to sort of think less about physical power and more about the psychic personality kind of thing. That’s the sort of phenomenon that we have, which shows some lack of analytical ability from my point of view.

Grégoire Canlorbe: A common belief is that the Japanese people is both indifferent to the culture of Western peoples—and genetically homogenous to the point of containing no genius. Yet contemporary Japan is displaying a variety of geniuses in videogames (like Shigeru Miyamoto), music (like Koji Kondo), etc., and is quite opened to the Western world culturally. Videogames like Zelda and Resident Evil are highly influenced by the West: the Western heroic fantasy in the case of the former; and George Romero’s movies in the case of the latter. Some Japanese actors (or movie directors) enjoy worldwide fame, like Hiroyuki Sanada who is portraying Scorpion in the new Mortal Kombat movie.

Kenya Kura: About the sort of personality and the intelligence mixture of the geniuses, I guess—Dr. Templeton and Edward Dutton—I’m sure that you talked with him—Edward Dutton wrote a very good book about why genius exists and what kind of mixture of personality and intelligence we need to make a real genius. And I do agree basically with Edward Dutton’s idea that we don’t have the sort of nice mixture of intelligence and, at the same time, a sort of very strong mindset to stand out from other people. The Japanese tend to be among others too much. So, they can’t really speak up and have a different kind of worldview from other people. As I said, Japanese scholars tend to rather avoid discussion or serious conflict of some point of view against other scholars so, that’s why there is no progress or no need to prove what you’re saying is true or not. That is a problem.

Okay, so, this is just a part of answering your question. And the other thing is—oh, but I’ve been talking about science—in order to be a scientist, you have to basically propose some kind of thesis and at least show some evidence that your thesis is right or proved in pieces. But when it comes to fine arts or Manga, Anime or literature or movies or games, you don’t really have to argue against other people. You just create what you feel is beautiful or great—whatever. So, because Japanese culture basically avoids discussions or arguments against each other, they are more inclined to create something like visual arts. That’s why I believe Japanese manga or anime have been very popular also among Europeans. Probably including yourself, right? I’m sure you’ve played or traded video games from Japan.

You talked about Hiroyuki Sanada. He’s one of the most famous action movie stars, like Tom Cruise type. So, I understand what you wrote, here. And the other thing is—it’s pretty much the same. In the Edo period, about 300 years ago, there was fine arts called ukiyo-e. These paintings and printings were sold to the public. And the French impressionists in the 19th century were, as far as I know, very attracted to those ukiyo-e and they got some inspirations from them and how to draw the lighting or nature itself. So, I do believe that Japanese people are probably genetically talented to some degree. I would dare to say they’re talented in visual arts. But it does not mean that they are talented in science. These activities are totally different, which gives me a very interesting sort of contrast.

Grégoire Canlorbe: In intergroup competition, the Empire of Japan was highly successful militarily—until 1945’s nuclear bombing, obviously. How do you account for that performance?

Kenya Kura: A German soldier was a very effective soldier, even compared with Americans or Swedes. So, I believe it’s very similar in the case of Japan. The Japanese tend to be tightly connected to each other, which gives them a very high advantage in military activity. That’s why they first tried to really dominate the whole of Asia, and, eventually, they had a war against the US in order to sort of get the whole Chinese continent. And, of course, Japan was defeated. But Japan is not so much endowed with natural resources like oil or coal, or whatever. In some sense, we’re very strong in military actions, it’s true. So, it’s very similar to the story that the Chinese are probably more inclined to study and learn original things like Confucius or the old stuff in order to show how intelligent they are, whereas the Japanese tend to be more war prone, more warmongers. They think more seriously and put more emphasis on military actions than the Chinese or Koreans. So, that’s why Japan, in the last century, first invaded Korea, and then, moved into the Chinese continent and defeated Chinese army. That’s just how I understand it. It’s very similar to German history.

Grégoire Canlorbe: Democracy is commonly thought to allow for an “open society” in which every opinion can be discussed—and in which ideological conflict can be settled through exclusively peaceful, electoral means, without the slightest drop of blood. Does the democratic regime in Japan since 1947 corroborate that vision?

Kenya Kura: You’re right. Exactly. You are French, so you have a serious understanding of how people can revolt against the ruling class because of the French Revolution, which is the most famous revolution in human history. So you have a serious understanding about the existence of conflict and that the product of this conflict may be fruitful, good for all human beings. But, unfortunately, Asia does not have that sort of culture that if you say something true and then, have a serious conflict of opinions about it, it may turn out to have a fruitful result. That’s very Western to me.

Grégoire Canlorbe: Thank you for your time. Would you like to add a few words?

Kenya Kura: I’ve probably said pretty much everything in a scattered manner, but let me emphasize one thing: usually, for any kind of European person, the Chinese, Koreans and Japanese look very similar or the same, but genetically, we are probably somewhat different, much as, for example, Slavic language people and the Germanic language group. So there might be some kind of microdifference of this kind which may, especially in the future, explain the dynamics of History. That is what I want to know and try to understand.

That conversation was initially published in The Postil Magazine‘s September 2021 issue

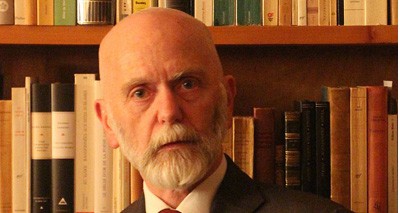

Jean Renaud Gabriel Camus, co-founder and President of the National Council of European Resistance, is a French writer and political theorist known for having coined the syntagm “great replacement”—referring to the colonization of Western Europe by immigrants from North Africa, Black Africa, and the Middle East. He was to be a speaker at the 2020 American Renaissance conference, which was canceled because of Covid.

Jean Renaud Gabriel Camus, co-founder and President of the National Council of European Resistance, is a French writer and political theorist known for having coined the syntagm “great replacement”—referring to the colonization of Western Europe by immigrants from North Africa, Black Africa, and the Middle East. He was to be a speaker at the 2020 American Renaissance conference, which was canceled because of Covid.

Davide Piffer is an evolutionary anthropologist. He obtained his BA in Anthropology from the University of Bologna and a Master of Science in Evolutionary Anthropology from Durham University. His Master’s thesis was on the sexual selection of sleep patterns among humans, and was the first to link mating behavior to chronotype within an evolutionary framework. His research effort later moved to quantitative genetics (i.e. twin studies), when he published one of the first accounts on the heritability of creative achievement. In 2013 he moved to molecular genetics, focusing on the polygenic evolution of educational abilities and intelligence and this is still his main focus. Within this research area, his main finding is that ethnic differences in intelligence are explained by thousands of genetic variants that predict cognitive abilities within populations. He has published a book of poems.

Davide Piffer is an evolutionary anthropologist. He obtained his BA in Anthropology from the University of Bologna and a Master of Science in Evolutionary Anthropology from Durham University. His Master’s thesis was on the sexual selection of sleep patterns among humans, and was the first to link mating behavior to chronotype within an evolutionary framework. His research effort later moved to quantitative genetics (i.e. twin studies), when he published one of the first accounts on the heritability of creative achievement. In 2013 he moved to molecular genetics, focusing on the polygenic evolution of educational abilities and intelligence and this is still his main focus. Within this research area, his main finding is that ethnic differences in intelligence are explained by thousands of genetic variants that predict cognitive abilities within populations. He has published a book of poems.

Richard Storey LL.M is a Catholic traditionalist, sometimes described as a medieval libertarian. His writing spans law, history, theology, and cultural criticism, and he is the author of The Uniqueness of Western Law: A Reactionary Manifesto. He lives in England with his wife and three children.

Richard Storey LL.M is a Catholic traditionalist, sometimes described as a medieval libertarian. His writing spans law, history, theology, and cultural criticism, and he is the author of The Uniqueness of Western Law: A Reactionary Manifesto. He lives in England with his wife and three children.

Richard Lynn is an English psychologist and author. A former professor emeritus of psychology at Ulster University and assistant editor of the journal Mankind Quarterly, Prof. Lynn is perhaps the world’s foremost proponent of eugenics. He is also well known for his studies of racial differences in intelligence. Many of his books have been

Richard Lynn is an English psychologist and author. A former professor emeritus of psychology at Ulster University and assistant editor of the journal Mankind Quarterly, Prof. Lynn is perhaps the world’s foremost proponent of eugenics. He is also well known for his studies of racial differences in intelligence. Many of his books have been