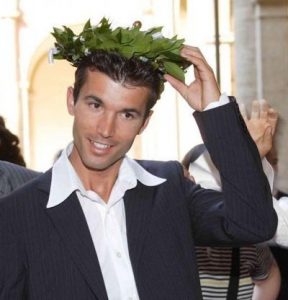

Davide Piffer is an evolutionary anthropologist. He obtained his BA in Anthropology from the University of Bologna and a Master of Science in Evolutionary Anthropology from Durham University. His Master’s thesis was on the sexual selection of sleep patterns among humans, and was the first to link mating behavior to chronotype within an evolutionary framework. His research effort later moved to quantitative genetics (i.e. twin studies), when he published one of the first accounts on the heritability of creative achievement. In 2013 he moved to molecular genetics, focusing on the polygenic evolution of educational abilities and intelligence and this is still his main focus. Within this research area, his main finding is that ethnic differences in intelligence are explained by thousands of genetic variants that predict cognitive abilities within populations. He has published a book of poems.

Davide Piffer is an evolutionary anthropologist. He obtained his BA in Anthropology from the University of Bologna and a Master of Science in Evolutionary Anthropology from Durham University. His Master’s thesis was on the sexual selection of sleep patterns among humans, and was the first to link mating behavior to chronotype within an evolutionary framework. His research effort later moved to quantitative genetics (i.e. twin studies), when he published one of the first accounts on the heritability of creative achievement. In 2013 he moved to molecular genetics, focusing on the polygenic evolution of educational abilities and intelligence and this is still his main focus. Within this research area, his main finding is that ethnic differences in intelligence are explained by thousands of genetic variants that predict cognitive abilities within populations. He has published a book of poems.

Grégoire Canlorbe: You have made a well-known attempt to provide a theoretical framework within which creativity—in science, philosophy, technology, music, mathematics, or literature—may be defined more precisely and measured. Could you present us your theory as it stands?

Davide Piffer: Creativity is not a single cognitive function or ability. Hence, it is not possible to measure creativity with paper and pencil or computer tests, unlike for example intelligence, or working memory. Creativity is the capacity to generate creative products, that is, scientific theories, poems, paintings, sculptures, inventions that are novel and useful or meaningful. Hence, the only way to measure a person’s creativity is via one’s creativity output (i.e. achievement) which is the sum of creative products over an individual’s (or society/ race) lifespan. A lot of cognitive abilities contribute to creativity, and in my seminal paper (Piffer, 2012), I argued that the widespread use by researchers of divergent thinking as the sole measure of creativity is a mistake. In fact, there are many cognitive and personality predictors of creative achievement besides divergent thinking, including IQ or general mental ability, working memory, openness to experience and non-clinical schizophrenic tendencies (i.e. “shizotypy” to use the psychiatrist’s jargon). Hypomania, or the tendency to feel positive emotions, has been linked to creativity, as well as bipolar disorder. All of these factors constitute what I call “cognitive potential”.

Divergent thinking (DT) is actually an important cognitive function which has been confined to creativity research. However it would benefit other areas of psychology as well. My opinion is that it would be better to regard DT as a form of intelligence, and to include divergent thinking measures in psychometric batteries and standardized intelligence tests (i.e. WAIS). Since psychometrically it is correlated to general cognitive ability but it taps into different neurological substrates, it would provide a more complete picture of one’s mental power, possibly less tied to academic intelligence and more to artistic or daily-life accomplishments.

From an evolutionary perspective, the ability to come up with many original ideas and find a novel way to light a fire or kill an animal would have increased people’s fitness more than the ability to say learn a mathematical equation or find the next number in a sequence. Moreover, divergent thinking predicts creative accomplishments above and beyond general intelligence, so the usual counter-argument by hard core “generalists” that it’s all about g doesn’t stand up from an evolutionary perspective.

As an anthropologist, I find it remarkable that a man’s intelligence as measured by IQ tests has practically no effect in increasing his attractiveness to women, whereas originality, sense of humour and other creativity-related features can increase a man’s attractiveness. This is possibly because they were better predictors of survival in the ancestral environment than conventional IQ-tests, which tap into some academic abilities that were not important for survival up until the creation of states with a high level of bureaucracy and the introduction of compulsory schooling. Another possibility is that artistic pursuits (which tap more heavily into divergent thinking abilities) were used by men to attract women. The sexy brain hypothesis has failed to find substantial support, but it does not have to be necessarily discarded, as it could have validity with regards to some specific cognitive abilities.

Another drawback of the “provinciality” of creativity research is that classical measures used in this field such as divergent thinking or creative achievement have been ignored by the currently hottest line of research, namely behavioral genetics and genome-wide association studies in particular. For example, the UK Biobank has hundreds of anthropometric and psychometric measures but it totally ignored creative achievement or divergent thinking.

Grégoire Canlorbe: As Leonardo da Vinci perspicaciously pointed out in his notebooks, “The black races of Ethiopia are not products of the sun, for if in Scythia a black man makes a child to a black woman, the offspring is black; but if a black man inseminates a white woman, the offspring is gray. Proof that the race of the mother has as much power over the fetus as that of the father.” Besides skin color, how do you sum up what we henceforth know—or appear to know—about heritable racial differences in traits like intelligence, creativity, or voice maturation?

Davide Piffer: As I said, creativity has been neglected by geneticists and many psychologists, so unfortunately we know next to nothing about race or individual genetic differences in creativity. With regards to intelligence, there is a growing consensus thanks to the work by myself and colleagues that racial differences have a genetic basis. This comes from different lines of evidence, using the most recent methods of population genetics: admixture analysis and polygenic scores.

Concerning voice maturation—Rusthon proposed the theory that the Mongoloids are the most K evolved and the Negroids are the least K evolved, while the Caucasoids fall intermediate between the two although closer to the Mongoloids. This theory is supported by a large amount of data. I made a new contribution to Rushton’s theory, in presenting race differences on the age at which the voice breaks in boys. The prediction from Rushton’s theory and the hypothesis to be tested is that the voice should break at a younger age in Negroids than in Caucasoids. The hypothesis was successfully corroborated.

Grégoire Canlorbe: Your most conclusive investigations in behavioral genetics are notably dealing with the connection between sexual selection and sleep patterns—or that between sexual selection and both sex– and country–level differences in performance on tests of fluid intelligence. Could you tell us more about it?

Davide Piffer: I was the first to investigate the relationship between sleep patterns and sexual behavior among humans as part of my MSc’s dissertation at Durham University. My original work was later replicated by a researcher from Sri Lanka and a group from Germany. Sleep is well known to affect mating behavior in many animal species, and some heritable differences in chronotype (the individual propensity to fall asleep and wake up early or late) also predict mating success among men, both in Western and non-Western societies. The effect seems to go above and beyond personality (extraversion) and the propensity to engage in social activities at night. Being a night owl is associated with going out at night, thus increasing the chances of meeting a member of the other sex, but also with testosterone levels. We still don’t know if it is also perceived as an attractive features in males, but it has significant sex differences, with males being more likely to be night owls than females across different societies, hence it is a candidate target for sexual selection.

Some years ago I published a paper where I put forward a theory with the goal of explaining the paradox that more developed countries, with high gender equality, had higher gender inequality in IQ scores. That is, males from more developed countries are smarter than women, but this sex difference is much smaller or absent in less developed countries: for example, in Muslim countries females have higher ability than males, so we could call this the Muslim paradox. This is the opposite of what one would expect from a purely environmental perspective, because gender equal countries give more educational opportunities to women. What I found was that smarter countries had higher gender differences independent of GDP or gender equality. It’s possible that ethnic differences in intelligence between countries are partly mediated by sexual selection, but I don’t think it’s due to female choice. It’s more likely a form of intra-sexual selection, whereby more intelligence males gain higher status or resources, translating into access to more females or ability to support more children.

Another potential mechanism that I did not mention in the paper but that occurred to me later is that in industrialized countries the dysgenic fertility is mainly driven by highly educated females having fewer chidren and later in their lives, whereas male intelligence is not a predictor of reproductive success. This sex disparity in dysgenic fertility would cause females to “dumb down” relative to males. From a purely genetic point of view, this is possible because many complex traits have sex-specific mechanism of expression, so that the same allele has different effects in males and females, even if the genes are not located on the sex chromosomes.

Grégoire Canlorbe: You suggested and devised a methodology to detect signals of polygenic selection—a mechanism that acts on multiple SNPs simultaneously—using educational attainment as an example. How do you summarize your approach?

Davide Piffer: My approach moves away from classical methods that focused on a single gene, because most characters are polygenic and the phenotypic effect is so diluted that you need to pull together many genetic variants in order to detect a pattern or a signal of selection. The frequency of a single allele is mainly affected by genetic drift unless that allele has a very strong effect on a trait, for example sickle-cell anemia. However, natural selection also affects population frequencies of alleles, but the effect on a single allele is typically so small that it can go unnoticed. However, when you pull together hundreds or thousands of alleles, you start seeing a pattern because the effects of random drift on each allele cancel one another out, and what is left is the directional effect of natural selection, which acts more strongly on some populations than on others, according to the environmental conditions or the sexual dynamics across the millennia. Of course these alleles are not picked at random from the genome, but they come from studies called GWAS (“genome-wide association study”) which explore the correlation between millions of genetic variants or SNPs (single-nucleotide polymorphisms) and some phenotype across very large samples (from 100 thousands to over a million individuals), such as years of education or height. These studies then find the SNPs with the strongest phenotypic effect, that is those that can increase an individual’s IQ by half an IQ point or height by a centimeter.

The average frequency of alleles weighted by their effect size on the phenotype (e.g. IQ) is the polygenic score. Polygenic scores can be used to predict how well individuals do in school, or their height or risk for cardiovascular disease. I calculated polygenic scores for populations by averaging the polygenic scores of samples from different ethnic groups available on public databases. In the case of educational attainment and intelligence, I used between 2400 and 3500 SNPs to compute polygenic scores, by focusing on the most significant SNPs.

What I found was that these population-level polygenic scores closely mirrored the scores on standardized intelligence tests across ethnic groups from all over the world. Ashkenazi Jews have the highest polygenic scores, followed by East Asians, then Europeans, South Asians, Native Americans and Blacks. These scores were also highly correlated to estimates of population IQ (r= 0.9), a result which occurs very rarely (odds of 1 to 46 thousands) with simulations that use random SNPs. Another important finding is that the SNPs with more significant effect had higher correlations with population IQ, a result that fits a selection account better than a neutral model of population differentiation.

Grégoire Canlorbe: Besides your inquiries in raciology and in other scientific fields, you happen to have a keen interest in Renaissance poetry—and even wrote a book of poems titled “Note d’alambicco.” Putting yourself in the footsteps of Galilei who compared your two favorite authors of the time in his Considerazioni al Tasso, how do you assess the respective literary merits of Tasso and Ariosto?

Davide Piffer: Galilei considered Ariosto’s work as superior to that of Tasso. In retrospect, his analysis was correct because literary critics and the public at large today usually prefer Ariosto. This is because Galileo the scientist liked the less flamboyant writing style and the ironical skepticism of Ariosto, as opposed to Tasso’s taste for words for their own sake and lack of realism. I think Galilei’s critique of Tasso was too harsh, as I can see his poetry had merits as well. Galilei knew the whole Orlando Furioso by heart, a “poem” over 38 thousand verses long divided into 46 canti. I found this impressive, especially considering I quit my attempt at memorizing it before I reached the end of the 1st canto. Memory and intelligence are positively correlated but not extremely well. It also seems like pre-modern people had much larger memories, perhaps for genetic reasons or because their mnemonic skills were not impaired by modern technology. Nowadays we can just google anything we can’t remember so there is not much pressure to learn things by heart.

Grégoire Canlorbe: It may be worthwhile to endeavor to measure race differences in imagination… for instance, through reporting and comparing the abundance—and the inventiveness—of metaphors in national poetic production. It may be worthwhile as well to investigate the correlation between scientific progress and what may be called the infrastructure of fantasy—the stock of dreams and legends with which a given nation is equipped. Do you sense that such inquiry would confirm Albert Einstein’s notion that “imagination is more important than knowledge” in occasioning scientific progress?

Davide Piffer: I think that imagination is more important than knowledge for scientific breakthroughs or revolutionary science, but in most labs around the world scientific progress is 99% perspiration and 1% inspiration. A more systematic approach would be to measure divergent thinking or creative achievement scores across ethnic groups but unfortunately none has made a systematic attempt at this.

Grégoire Canlorbe: You made the claim that the north-south difference in Italy in fluid intelligence should be understood in terms of genetic differences between the populations of north and south Italy. Could you come back to the data corroborating that hypothesis?

Davide Piffer: Historically, literacy levels and economic prosperity have been higher in the north than in the south. Data collected by Richard Lynn have shown that these differences are reflected in scores on tests of intelligence and scholastic aptitude (PISA and INVALSI).

There are strong genetic differences within Italy, recently corroborated by an in-depth study (Raveane at al., 2019), which were mostly established by pre-Roman times: Bronze-Age migrations from the Eastern European steppes (Indo-Aryans) in the north and West Asians from the Caucasus in the south. The Latin people that founded ancient Rome belonged to this Indo-European/Aryan group, along with other Italic tribes (the Veneti that later founded Venice).

Later migrations strengthened the pre-existing differences: in the first millenium BC, groups of Celtic people (originating from Indo-Aryans, like the native northern Italians such as the Veneti and the Ligurians) settled in the north and admixed with their ethnic cousins (that is why the Roman name for northern Italy was Gallia Cisalpina), and the Greeks heavily colonized the South (Magna Graecia) in the 1st millenium BC. In the Middle Ages, Germanic people invaded Italy and mostly added to the genetic pool of northern Italy (mostly Lombards and Gothic people) with some pockets in central and southern Italy (the Lombards in the Ducato di Benevento and the Normans in Palermo), whereas the south was conquered by the Arabs.

Grégoire Canlorbe: It has been hypothesized that race differences in ethnocentrism should be connected to two opposite models of group selection… the first one consisting in preserving the genetic homogeneity—and therefore the ethnocentrism through kin solidarity—of society at the expense of a gene pool which be sufficiently diversified to allow for the emergence of geniuses; and the second one consisting for its part in sustaining—at the expense of kin solidarity and therefore ethnocentrism—a more diversified gene pool which would promote the occurrence of geniuses.

In view of its undeniable success—since the days of Ancient Rome—in conciliating kin solidarity (through the persistence of extended, instead of nuclear, families), and high levels of ethnocentrism, with a “culture of genius” from which sprang some of the greatest minds of humanity, Italian civilization seems to be puzzling when confronted with such theoretical framework. Should one abandon the beautiful theory?

Davide Piffer: I am not very familiar with this theory but I am not sure that ethnocentrism would necessarily hinder the development of a sufficiently diversified gene pool to allow the emergence of geniuses. Jews are highly ethnocentric but they have the highest percentage of geniuses than any other ethnicity, as shown by Richard Lynn (2011). Also, let’s remember that Italy was settled throughout history by people of different ethnic backgrounds: Neolithic farmers, Bronze Age steppe pastoralists, Celtic and Germanic tribes, Arabs, etc. Moreover, Italy reached political unity only relatively recently and each region developed its own genetic landscape thanks to drift, migrations and local selection. A very recent study found that Italy has the largest degree of genetic population structure so far detected in Europe (Raveane at al., 2019). So Italy conciliated relatively high degrees of kin solidarity with an extremely diverse gene pool thanks to its geographic position and historical events. I think this could solve your paradox.

Grégoire Canlorbe: Thank you for your time. As an anthropologist who conducted some experiments on clairvoyance, do you subscribe to the classical teaching of the Church that suprasensible precognition is linked to the intervention of an angel? Or do you rather adhere to a genetic origin of the clairvoyance gift… with the possibility of ethnic differences in clairvoyance (leading Jews and Russians to display the highest ability for clairvoyance)?

Davide Piffer: I did not explore the topic of ethnic differences in clairvoyance, because we have not yet clarified its individual correlates. I certainly rule out the religious explanation and if they existed, they would be abilities related to intuition. However, there seems to be large variability between people in this ability, with most people being very weak and only rare individuals showing results consistently higher than chance.

References:

Piffer, D. (2012). “Can creativity be measured? An attempt to clarify the notion of creativity and general directions for future research.” Thinking Skills and Creativity, 7, 258-264.

Raveane et al. (2019). “Population structure of modern-day Italians reveals patterns of ancient and archaic ancestries in Southern Europe.” Science Advances, DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.aaw3492

Lynn, R. (2011). The Chosen People: A Study of Jewish Intelligence and Achievements. Augusta, GA: Washington Summit Publishers.

That conversation was first published on American Renaissance (in a slightly different version), in November 2019