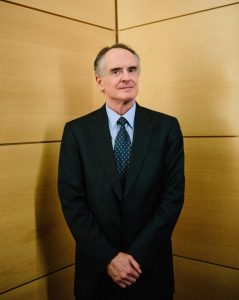

Ricardo Duchesne is a Canadian historical sociologist and professor at the University of New Brunswick. His main research interests notably include the Indo-European aristocratic-warlike and individualist ethos, the Faustian mentality and the creativeness of Western civilization from ancient Greek times to the present, and the pernicious effects of the multicultural and multiracial ideal on modern Western society.

Ricardo Duchesne is a Canadian historical sociologist and professor at the University of New Brunswick. His main research interests notably include the Indo-European aristocratic-warlike and individualist ethos, the Faustian mentality and the creativeness of Western civilization from ancient Greek times to the present, and the pernicious effects of the multicultural and multiracial ideal on modern Western society.

This conversation was first published on Kevin B. MacDonald’s The Occidental Observer (in three parts), on 31 January 2019. It was also printed in The Occidental Quaterly.

Grégoire Canlorbe: In your eyes, the European civilization of the White man has been systemically downsized by contemporary world historians—to name but a few, Patrick O’Brien, Sebastian Conrad, or Ian Morris. Could you develop?

Ricardo Duchesne: At this point in time, the downplaying of European civilization goes well beyond the observations I made in The Uniqueness of Western Civilization (2011). The globalist establishment is no longer satisfied with the replacement of Western Civ courses, which were part of the standard curriculum in North America throughout much of the twentieth century, with Multicultural World History surveys that emphasize “reciprocal connections within the globe.” The academic establishment is no longer satisfied instructing students that European achievements can only be understood in connection with the rest of the world’s cultures, that Muslims were key creators of the West no less than Christians, that the Scientific Revolution, the Enlightenment, and the Industrial Revolution, were world historical affairs, that Europe only managed to industrialize thanks to the resources and hard labor of Africans and Aboriginals. That is no longer enough, they are now insisting, as I indicated in my second book, Faustian Man in a Multicultural Age (2017), that Europeans don’t have a distinctive identity because they have been mixing racially for thousands of years as a result of migratory movements. They are forcing their students to equate the current state-sponsored immigration movements from the Third World, purposely aimed at diversifying all White nations, with internal European migrations that occurred over the course of many centuries. They are trying to strip Europeans of any sense of ethnic identity, by making them believe that the race-mixing globalists are incessantly promoting today is a natural continuation of migratory movements thousands of years ago.

[Read more…] about A conversation with Ricardo Duchesne, for The Occidental Observer

Greg Johnson, Ph.D., is editor-in-chief of

Greg Johnson, Ph.D., is editor-in-chief of

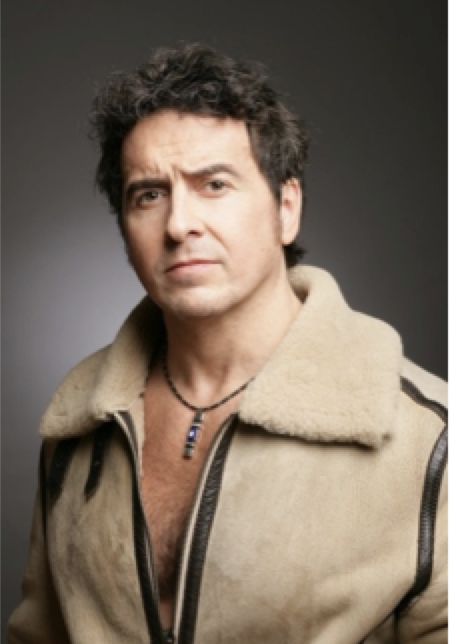

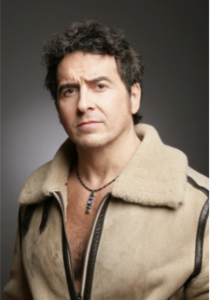

Frédéric Delavier is a French author of books on bodybuilding, who also became a philosopher. His book Guide to Bodybuilding Movements first published in 1998 was a worldwide bestseller with over 2 million copies sold. It has been translated into more than 30 languages. Frédéric Delavier is also known as an educational or critical videographer on his

Frédéric Delavier is a French author of books on bodybuilding, who also became a philosopher. His book Guide to Bodybuilding Movements first published in 1998 was a worldwide bestseller with over 2 million copies sold. It has been translated into more than 30 languages. Frédéric Delavier is also known as an educational or critical videographer on his

Samuel Jared Taylor is a Japan-born American white advocate. He is the founder and editor of the online magazine

Samuel Jared Taylor is a Japan-born American white advocate. He is the founder and editor of the online magazine