Laurent Alexandre is a French surgeon-urologist, essayist, and entrepreneur. The founder of the Doctissimo website, he is interested in the transhumanist movement and in the upheavals that humanity could experience, along with the progress of science in the field of biotechnology. His latest book is L’IA va-t-elle aussi tuer la démocratie [Will AI kill democracy as well]?

Laurent Alexandre is a French surgeon-urologist, essayist, and entrepreneur. The founder of the Doctissimo website, he is interested in the transhumanist movement and in the upheavals that humanity could experience, along with the progress of science in the field of biotechnology. His latest book is L’IA va-t-elle aussi tuer la démocratie [Will AI kill democracy as well]?

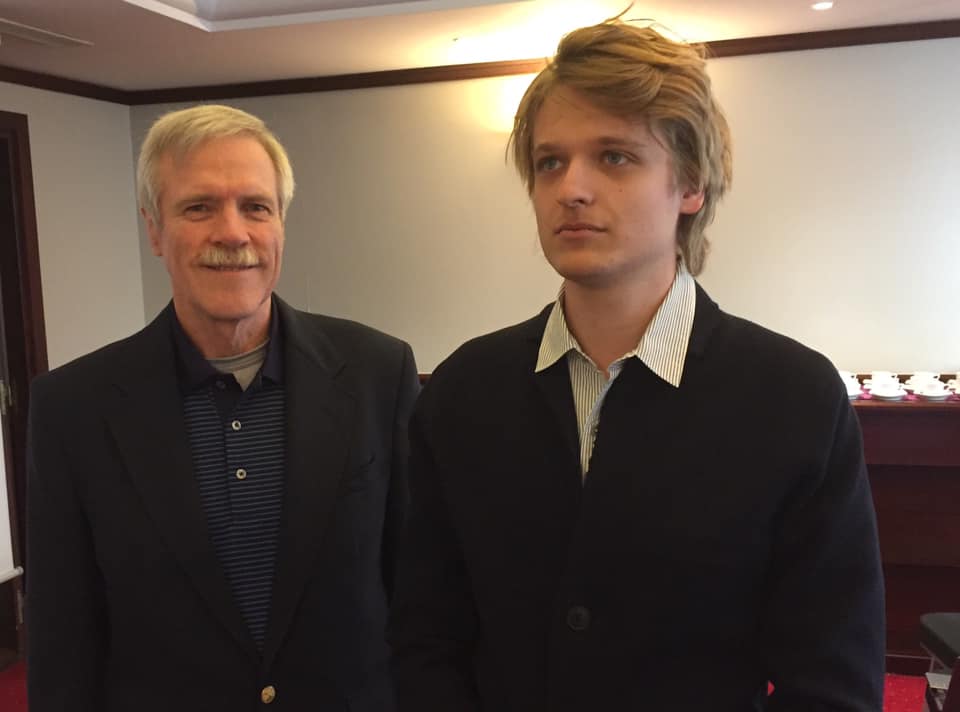

Grégoire Canlorbe: It should be remembered that Nietzsche saw in birth control, as well as in the non-assistance of weak elements (in terms of physical or mental abilities) in our society, an unavoidable aspect of the superhuman culture which he was calling for. As a supposed transhumanist, do you regret the collapse of the eugenic movement in the 1950s?

Laurent Alexandre: I do not believe that the 1950s are a period of decline of eugenics, they are rather a period of mutation of eugenics. When Julien Huxley invents the word “transhumanism” in 1957, it is for the purpose of creating left-wing eugenics… namely egalitarian eugenics. The 1950s did not see eugenics receding after the horrors of Nazism: they saw right-wing eugenics mutate into a leftist eugenics, dubbed “transhumanism” by Huxley.

Grégoire Canlorbe: The alleged responsibility of human carbon emissions for contemporary warming is a subject that is conducive to raising the temperature in debates. Could you remind us of the main lines of your Promethean (or Faustian) reassessment of climate policy: namely a reassessment that does not deny the need to mitigate the greenhouse effect supposedly linked to CO2 emissions, but which attempts to conciliate climate action, the industrial and cognitive domination of nature, and materialistic enjoyment?

Laurent Alexandre: Controlling CO2 emissions is going to be incredibly complicated. One is going to spend several very difficult decades. And if indeed, as I believe, there is a link between CO2 and climate, we will not be able to reduce CO2 emissions before 2050. We will have climate concerns probably until the end of the century.

First of all, collapsologists overestimate the social body’s acceptance of a CO2 reduction policy. We have seen what means a tiny drop in the purchasing power of Yellow Vests to fight against the greenhouse effect: one imagines what would give a drop of 30 to 40% of the purchasing power of the lower classes. One would have a real revolution, which would probably be a far-right revolution rather than an extreme-left one in the current context. A degrowth policy will therefore be very hardly accepted… and one can see that all the polls show that the priority of the French is the purchasing power before the ecological transition.

[Read more…] about A conversation with Laurent Alexandre, for The Council of European Canadians

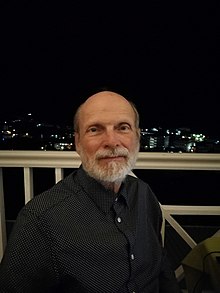

John Raymond Christy is a climate scientist at the University of Alabama in Huntsville (UAH) whose chief interests are satellite remote sensing of global climate and global climate change. In February 2019 he was named as a member of the EPA Science Advisory Board.

John Raymond Christy is a climate scientist at the University of Alabama in Huntsville (UAH) whose chief interests are satellite remote sensing of global climate and global climate change. In February 2019 he was named as a member of the EPA Science Advisory Board.

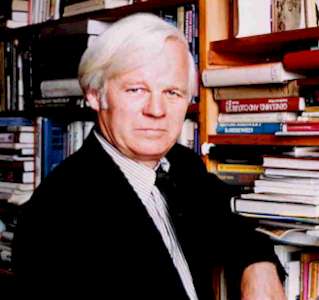

Richard Lynn is an English psychologist and author. A former professor emeritus of psychology at Ulster University and assistant editor of the journal Mankind Quarterly, Prof. Lynn is perhaps the world’s foremost proponent of eugenics. He is also well known for his studies of racial differences in intelligence. Many of his books have been

Richard Lynn is an English psychologist and author. A former professor emeritus of psychology at Ulster University and assistant editor of the journal Mankind Quarterly, Prof. Lynn is perhaps the world’s foremost proponent of eugenics. He is also well known for his studies of racial differences in intelligence. Many of his books have been

Kevin B. MacDonald is an American psychologist. A retired professor of psychology at California State University, Long Beach (CSULB), he is best known for writings that characterize Jewish behavior as a “group evolutionary strategy.”

Kevin B. MacDonald is an American psychologist. A retired professor of psychology at California State University, Long Beach (CSULB), he is best known for writings that characterize Jewish behavior as a “group evolutionary strategy.”

Michael H. Hart is an American astrophysicist, historian, and white separatist militant. He is mostly known for the Fermi-Hart Paradox, and his books The 100: A Ranking of the Most Influential Persons in History and Understanding Human History. He was a

Michael H. Hart is an American astrophysicist, historian, and white separatist militant. He is mostly known for the Fermi-Hart Paradox, and his books The 100: A Ranking of the Most Influential Persons in History and Understanding Human History. He was a