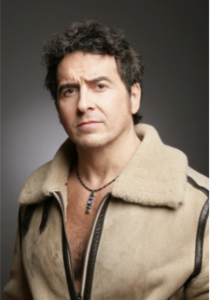

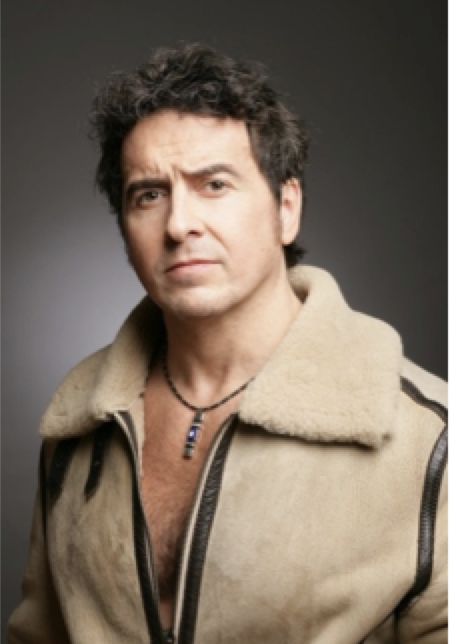

Frédéric Delavier is a French author of books on bodybuilding, who also became a philosopher. His book Guide to Bodybuilding Movements first published in 1998 was a worldwide bestseller with over 2 million copies sold. It has been translated into more than 30 languages. Frédéric Delavier is also known as an educational or critical videographer on his YouTube channel. He recently published a treatise in philosophy, The awakening of consciousnesses [in French: L’Éveil des Consciences], which is awaiting translation into English. The following interview was first published on Counter-Currents Publishing.

Frédéric Delavier is a French author of books on bodybuilding, who also became a philosopher. His book Guide to Bodybuilding Movements first published in 1998 was a worldwide bestseller with over 2 million copies sold. It has been translated into more than 30 languages. Frédéric Delavier is also known as an educational or critical videographer on his YouTube channel. He recently published a treatise in philosophy, The awakening of consciousnesses [in French: L’Éveil des Consciences], which is awaiting translation into English. The following interview was first published on Counter-Currents Publishing.

Grégoire Canlorbe: Could you start by telling us about what motivated your decision to pursue a career in sculpting the body and in writing books on the subject?

Frédéric Delavier: To tell the truth, I have never been a bodybuilder, despite the fact that everyone presents me as such. I do bodybuilding because I like it, and because I like to walk around with a solid form; but I never wanted to have a bodybuilder physique. When I started bodybuilding in my youth, I saw it as a complement to the combat sports that I practiced: a way to increase my strength and therefore my dangerousness on the tatami. I naturally frequented, and observed, bodybuilders on this occasion.

[Read more…] about A conversation with Frédéric Delavier, for Counter-Currents Publishing

Samuel Jared Taylor is a Japan-born American white advocate. He is the founder and editor of the online magazine

Samuel Jared Taylor is a Japan-born American white advocate. He is the founder and editor of the online magazine

Guillaume Faye is a French philosopher, known for his pro-Zionism right-wing paganism, his call for a Eurosiberian Federation of white ethno-states, or his concept of archeofuturism, which involves combining traditionalist spirituality and concepts of sovereignty with the latest advances in science and technology.

Guillaume Faye is a French philosopher, known for his pro-Zionism right-wing paganism, his call for a Eurosiberian Federation of white ethno-states, or his concept of archeofuturism, which involves combining traditionalist spirituality and concepts of sovereignty with the latest advances in science and technology.

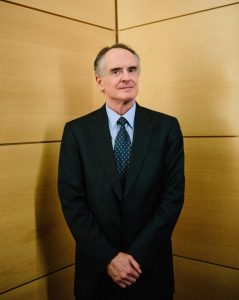

Richard Siegmund Lindzen is an American atmospheric physicist known for his work in the dynamics of the atmosphere, atmospheric tides, and ozone photochemistry. He has published more than 200 scientific papers and books. From 1983 until his retirement in 2013, he was Alfred P. Sloan Professor of Meteorology at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. He was a lead author of Chapter 7, “Physical Climate Processes and Feedbacks,” of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s Third Assessment Report on climate change. He has criticized the scientific consensus about climate change and what he has called “climate alarmism.”

Richard Siegmund Lindzen is an American atmospheric physicist known for his work in the dynamics of the atmosphere, atmospheric tides, and ozone photochemistry. He has published more than 200 scientific papers and books. From 1983 until his retirement in 2013, he was Alfred P. Sloan Professor of Meteorology at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. He was a lead author of Chapter 7, “Physical Climate Processes and Feedbacks,” of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s Third Assessment Report on climate change. He has criticized the scientific consensus about climate change and what he has called “climate alarmism.”