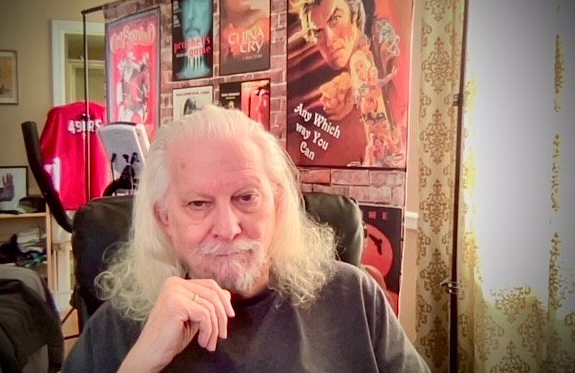

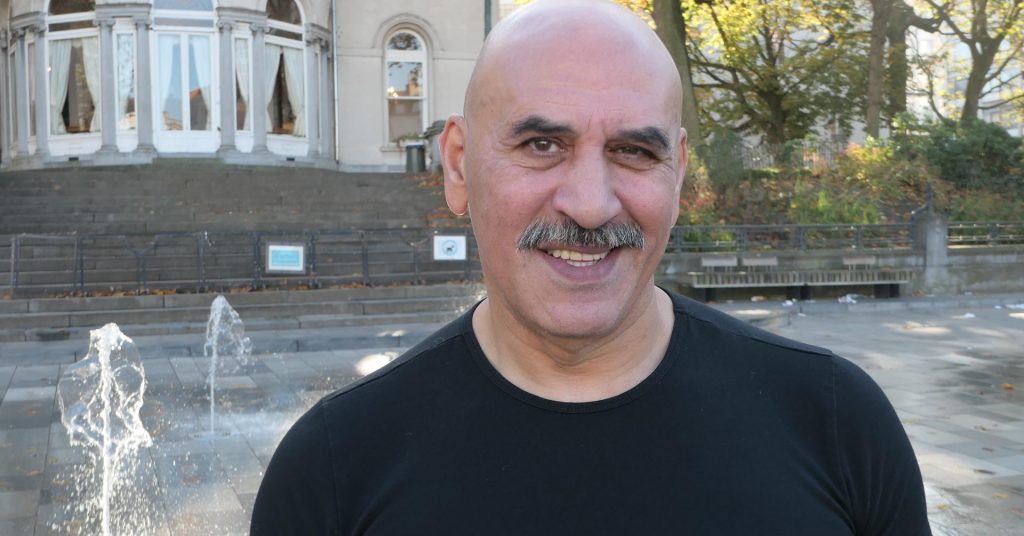

Ron Smoorenburg is a Dutch martial artist, actor, stuntman, and fight choreographer. He is notably known for his respective fights with Scott Adkins in Ninja: Shadow of a Tear, with Michael Jai White in Never Back Down: No Surrender, and—above all—with Jackie Chan in Benny Chan’s and Jackie Chan’s Who Am I? He currently lives in Thailand.

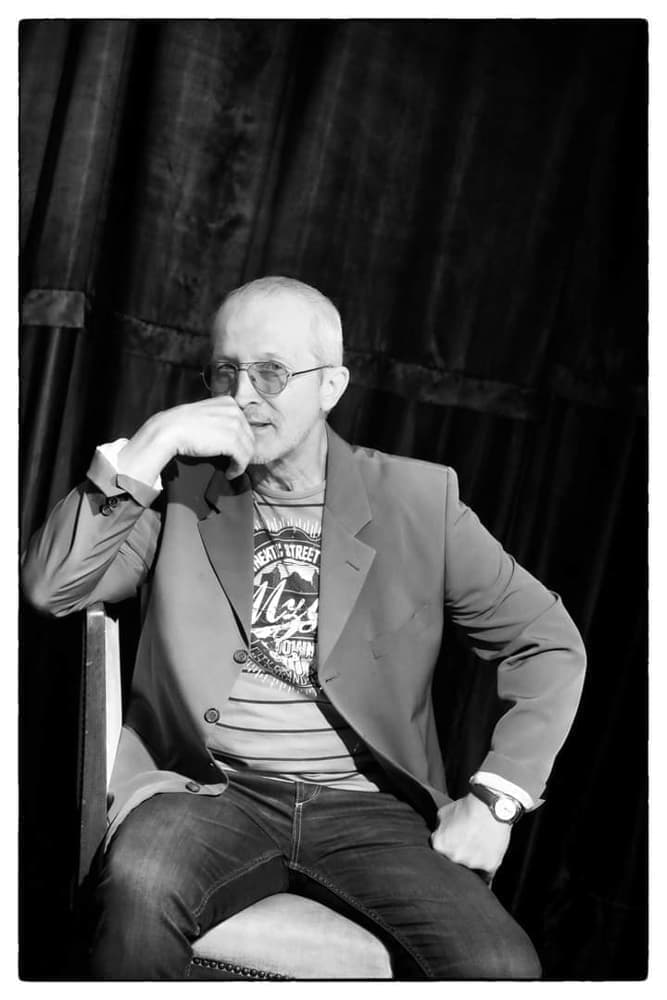

One the newest projects Ron Smoorenburg is being involved with, here as an actor, is feature Funayurei, which is being directed by Abel Ernest Tembo from a screenplay by Grégoire Canlorbe.

Grégoire Canlorbe: You started your practicing martial arts at the early age of seven, in Netherlands. At the time of your youth, were martial arts, and those movies centered on martial arts, as popular in Netherlands as they were, say, in America?

Ron Smoorenburg: Actually it was the best time ever in the 80’s early 90’s and I’m very happy to be born in this generation. These days movies were motivating, actors looked ripped and movies had great training sessions on music, there were lots of martial art movies on VHS video cassette, I remember watching Karate Kid on a birthday party and we all stood up and jumped around doing kicks, a start of a journey which never stopped since then. We also had this series called ‘The Master’ a ninja tv series, all the kids were making ninja stars and literally playing ninja outside. When I was 12 I saw Young master on tv from Jackie Chan and a few years later JCVD’s Bloodsport came out and No Retreat No Surrender movies we basically watched everyday till there was no sound anymore.

Grégoire Canlorbe: How did Jackie Chan notice you, and end up hiring you to play the strongest of the two opponents at the end of Who Am I?

Ron Smoorenburg: My boss in the office I worked saw an article about Jackie Chan casting for 300 extras in his movie shooting in Holland. I asked half a day off to send a letter and pictures to the agency in Rotterdam. After pushing a lot I was chosen out of 1000 applicants to become an extra.

I had to play 3 days as a business guy in the background and you can actually see me in one of the scenes. After the Dutch local stunt team laughed about my ambition and literally ridiculed me I asked one of the JC team members if I can do action, he asked me to give him a showreel. I was a graphic designer so the same night I made up a cover like I was already some kind of action guy in movies. I just had the record highest (kick 11 feet) on national tv and I always did movie fight demo’s on martial art events. I also was the first Karateka doing a free style Kata – A karate form on music and I had all of this on tape.

And the next day after the team of JC saw the video in a lunch break they called me over to do the same moves live in front of them. They said I was the best out of 20 guys auditioning for the role of the final fight scene. 10 minutes later someone came to take measurements for the suit I had to wear in the final fight. It was like winning the lottery but another challenge emerged.

Grégoire Canlorbe: Did you have some trouble adapting to the quick rhythmic movements of Jackie Chan?

Ron Smoorenburg: To answer this question the best is that you can compare it with putting someone in a racecar who never drove a Formule 1 race. Even though I am a martial artist all my life, fighting someone like Jackie, top of the top level in a 1st movie ever is definitely a challenge.

I was always looking at JCVD doing splits high kicks, and JCVD doesn’t really use these rhythms Jackie uses. Even action veterans like Scott Adkins and Eric Jacobus admit that this HK style isn’t easy in the beginning and especially fighting these stars with the added pressure as well.

I managed to pick it up. Sadly in the beginning they let another stuntman Brad Allen do a combo for me which I wasn’t even allowed to try before Jackie got a little upset, in the documentary they reversed it so they show Jackie got t little upset then bringing the stunt double, but that wasn’t the case so I felt a little bit hurt by this and it did even affect my career a little.

In reality every stuntman should know that fighting Jackie isn’t easy and even his team members came to me saying after 15 years they were still nervous fighting Jackie. So what can we do? I have to see it positively and learning the hard way and having lots of pressure is part of the game sometimes. This is my big dream and no one will take it away, that’s why I never stopped.

To be honest every movie after this experience was more easy as I was used to this huge amount of pressure. I can tell you even people who are in the stunt biz for years would still have a challenge right now if they have to fight Jackie, believe me.

Grégoire Canlorbe: What is your view of the evolution of Jackie Chan’s career following the retrocession of Hong Kong?

Ron Smoorenburg: I think he should leave politics to the politicians, he came from HK and he has a huge fanbase there, and things are sensitive.

Grégoire Canlorbe: How did it feel to act as a villain in Clarence Fok Yiu-leung’s Martial Angels?

Ron Smoorenburg: Actually he gave me a hell of an opportunity but with acting I was still beginning so I definitely could have done better now. It was a cool movie with 7 action girls and a great concept.

Grégoire Canlorbe: Please tell us about the backstage of that fight in Prachya Pinkaew’s Tom-Yum-Goong in which you’re one of many fighters facing Tony Jaa.

Ron Smoorenburg: When I came to Thailand to do a European tv series, I visited the set of this movie and met the director Prachya, I literally did the same as I did with Who am I? I had to show some moves to the director and they asked me if I was ok to be in a group fight because they already shot all other fights, I was happy to be doing action in Asia and with a cool action star like Tony Jaa so I agreed. We got on really well. He actually gave me a real good kick straight in the face and that was very memorable.

Grégoire Canlorbe: How do you account for the popularity of Thailand when it comes to choosing the main location for the plot in an action movie?

Ron Smoorenburg: Thailand got it all, urban, forest, alleys, rooftops, mountains, beaches, also some very gritty and characteristic streets in Bangkok from rough to high class. You can get a lot of things done in Thailand.

Grégoire Canlorbe: After spending so many years in Thailand, do you sense your heart and soul have become those of a Thai man?

Ron Smoorenburg: Yes I have this sense of freedom and life which I don’t find in the west, Bangkok is alive day and night, I train in the night, also the Thai smile and general happiness is here for a fact and when I go back to Holland I see people running faster and looking more serious to be honest.

Grégoire Canlorbe: You acted in Nicolas Winding Refn’s Only God Forgives. Esthetically speaking, how do you assess the fight opposing Vithaya Pansringarm to Ryan Gosling?

Ron Smoorenburg: I’m not a fan of it, its not really memorable, I feel its just choreo to be choreo.

Grégoire Canlorbe: Do you share the common line of criticism that the way of filming the stunt and action stuff in John Wick movies lacks any true artistic dimension, thus boiling down to a mere “technician” work?

Ron Smoorenburg: I felt that for the first 3 parts, there were no rewinders for me like the movies I described when I was young. But John Wick 4, did change it for me, having people like Donnie Yen, Scott Adkins, Marko Zaror they gave flavor to it. The other JW parts were more like ok there’s another guy in a black suit coming, and you just know he’s going to lose the same way as all the others did.

Grégoire Canlorbe: You fought Scott Adkins in Ninja: Shadow of a Tear. How was the fight choreographed, executed, and shot? How do you sum up what makes the prowess of Isaac Florentine in filming action?

Ron Smoorenburg: This was a scene where we had to do all in 1 take and this is very cool that Isaac did this together with Choreographer Tim Man who is a genius. It was shot very well and we did have 1 rehearsal for it (Not like Jackie Chan where they do it straight away on the spot) In the original choreo I actually did a few jump kicks, but it was cut for some reason, its sad because I also like to show stuff. Still this fight is very nice and Scott Adkins is a beast (endurance wise) when it comes to shooting.

Grégoire Canlorbe: You acted in Michael Jai White’s Never Back Down: No Surrender, in which you fought White himself. How do you assess Michael Jai White as a movie director, and as a martial artist?

Ron Smoorenburg: I felt he was very good at punches besides his kicks, he’s a real martial artist and you can see and feel he loves it. Also to me he’s always a gentleman.

Grégoire Canlorbe: In Street Fighter: The Legend of Chun-Li, you acted alongside the late Michael Clarke Duncan. Did you have much interaction with him behind the camera?

Ron Smoorenburg: Not too much but he was always smiling, he’s super humble and what a personality. Also if you see where he came from before he became an actor it’s more than respect what he did.

Grégoire Canlorbe: To you, does Desperate Housewife’s Neal McDonough’s portrayal of Bison in Street Fighter: The Legend of Chun-Li compare with that of Raúl Juliá in Street Fighter?

Ron Smoorenburg: No it doesn’t work, they shouldn’t do these things.

Grégoire Canlorbe: You were cast in Death Note: L Change the Word. Did you read the manga, Death Note?

Ron Smoorenburg: Yes it’s super cool and I’m happy to be part of it.

Grégoire Canlorbe: How did you enter the world of Bollywood? How does it feel to be part of the latter?

Ron Smoorenburg: We have Bollywood movies shooting in Thailand, and some directors remembered me and the stunt team and ask us to came over to Bollywood and south India for other movies. It’s always a challenge getting your money though in 90% of the cases to be honest. And they are not that safe as well. The coolest movie I did was definitely Brothers with Akshay Kumar with a cool MMA fight in the ring. That movie also had good drama and was a remake of Warrior.

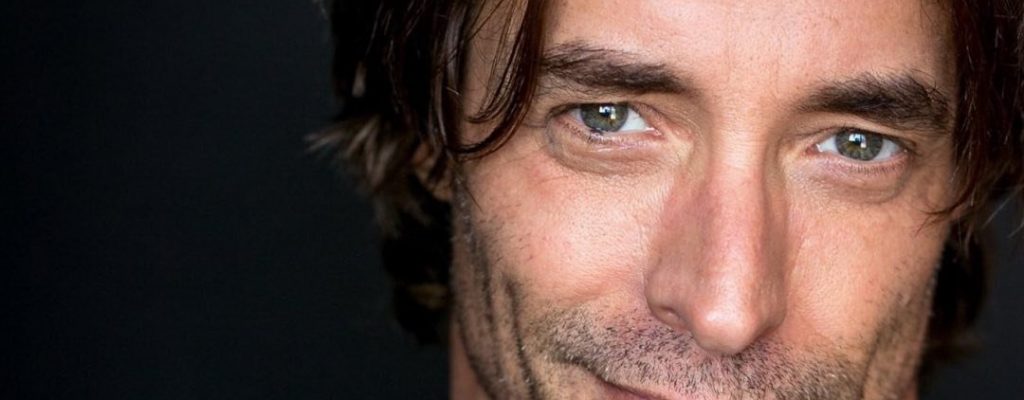

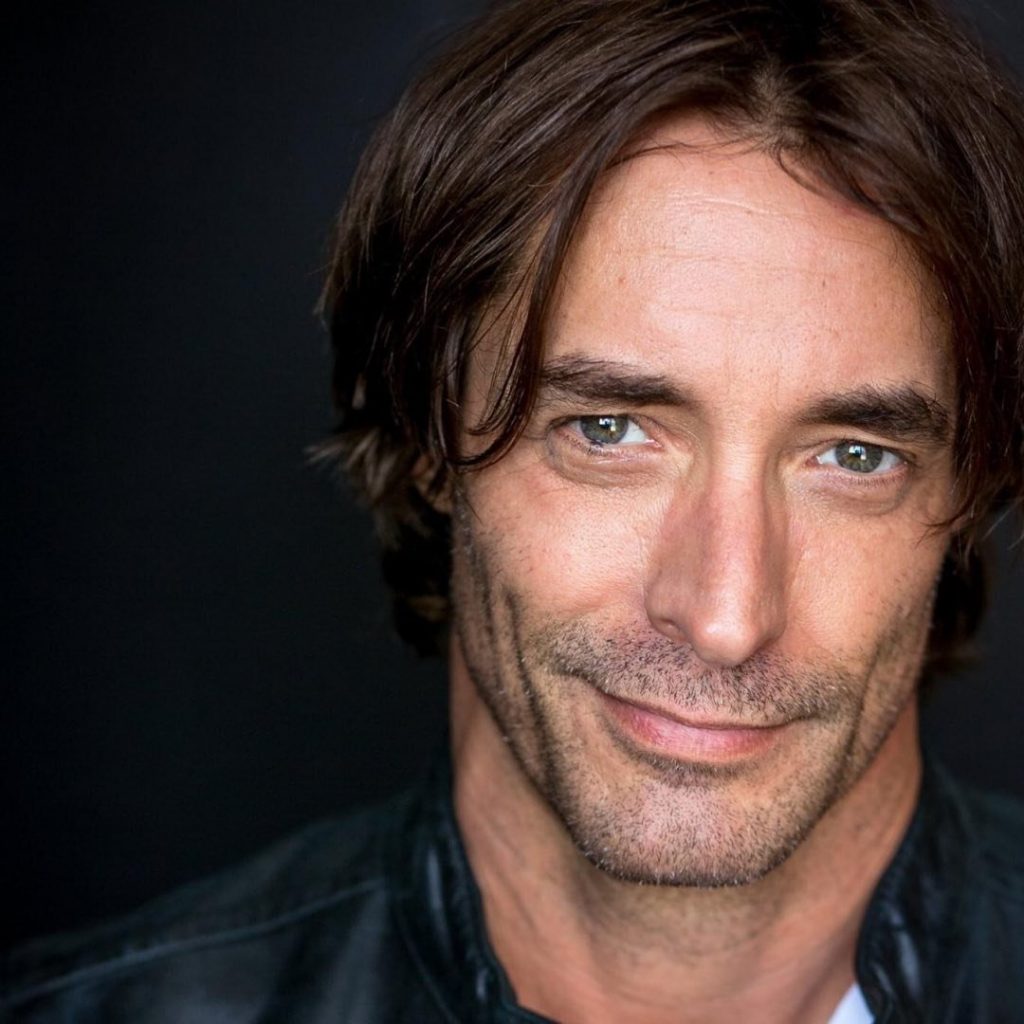

Grégoire Canlorbe: What can you tell us of that new project you’re being involved with as an actor, alongside Mark Stas—Funayurei?

Ron Smoorenburg: I’m very excited about this project as I will fight alongside Mark. Mark is amazing and for me a new action star not less than Donnie Yen, Jackie or Jet Li, for real. Marks action style and adaptation, implementation is amazing. Real time on the spot he can even adapt if needed. He’s a true master. I actually contacted him years ago and he came to Thailand, We did 2 big fights in English Dogs the movie and it’s very memorable. We always look out for the next time to fight and one of the main reasons I upgrade myself so hard is to prepare for my next fight.

I created my own movie style Recharge and I feel it’s the perfect to fight Mark with Wing Flow. I love Mark and really he deserves all the best. Having Mark is having a Diamond on board. Every investor/director/producer should be very happy to have him, and I’m happy to work alongside or fight with him.

Grégoire Canlorbe: Thank you for your time. Is there anything you would like to add?

Ron Smoorenburg: Currently RECHARGE, the fighting style I developed is going really well, its based on chain lighting and has lots of unique combos and some unique kicks I designed from scratch. The message I have for performers and artists is to always be unique and creative, never follow the herd. Now I’m going to USA with my Management, Hollywood productions, Varol Porsemay to set a foot on the ground there. I realize I have to offer something, that’s why I work day and night on it. It’s like as a car which can have a nice a cover but also needs a good engine. The stronger the engine is the better the car, so keep working on yourself, and with Love… you get what you can carry. As I always say, LIFE IS ACTION.

That conversation was originally published by Bulletproof Action, in April 2023