David Salucci is a French martial artist, strength coach, actor, and writer.

A 6th-dan black belt in Shotokan karate and a World and European Champion in semi-contact kickboxing, he has spent more than four decades pursuing a path where the body becomes an extension of the mind. Holder of eighteen federal certifications in coaching, martial arts, and physical conditioning, he also trained in Mexico with the Tepic Federal Police, where he obtained his international APR licence.

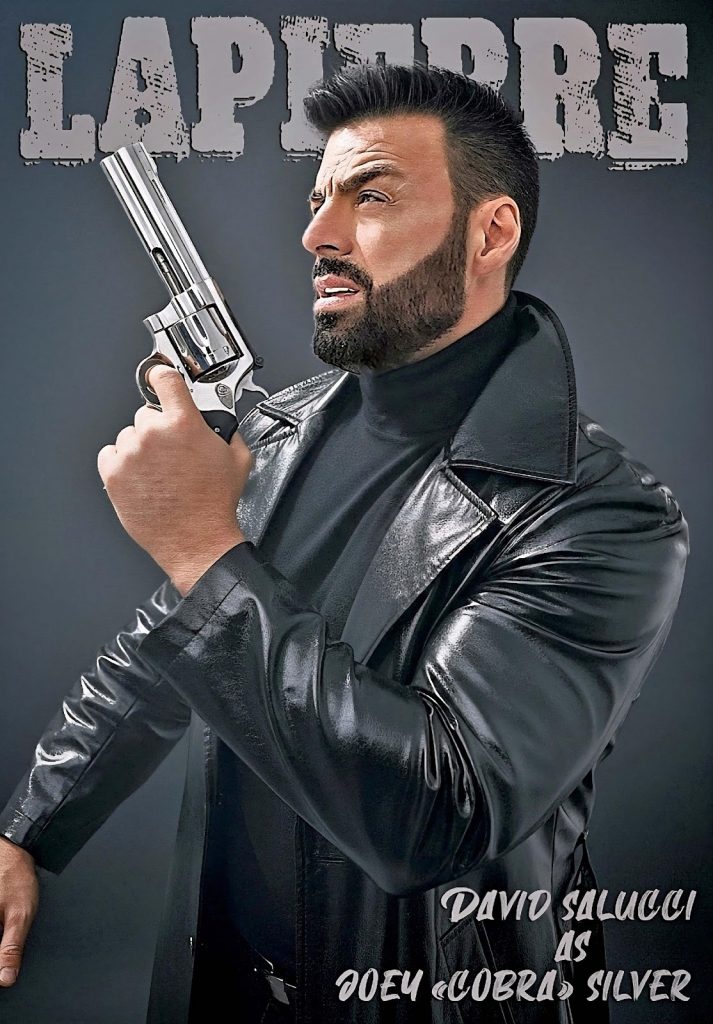

His artistic journey follows the same inner discipline: he appears in The Shepherd Code: Lapierre (IMDb), the final chapter of Alan Delabie’s trilogy, bringing to the screen the same intensity he has long cultivated on the tatami.

Author of Philosophical Treatise, The Path of Integrity (Amazon), David Salucci explores in his writings the bond between strength and righteousness, the dialogue between physical rigor and the clarity of the soul. On his personal blog (davidsalucci.blogspot.com), he extends this reflection, weaving together spirituality, introspection, and a lucid perspective on the contemporary world.

Grégoire Canlorbe: Please tell us about your collaboration with Alan Delabie.

David Salucci: Alan and I have known each other for about six years. He is a former martial artist, shaped by the stage and by the art of the nunchaku, his trademark discipline, but also by everything the martial path demands: mastery, rigor, and humility. As for me, I am a pure product of karate. Naturally, that gave us common ground from the very beginning.

At that time, Alan was steadily gaining momentum, project after project, climbing the ranks of a field as demanding as it is fascinating. Through our conversations, we discovered a shared set of values, a similar relationship to discipline, loyalty, and effort. The bond formed without calculation. What began as simple exchanges turned into daily conversations, and from those conversations emerged a genuine friendship. Something strong, almost fraternal.

The Lapierre project brought us together without premeditation. At first, neither of us imagined we would ever collaborate in a cinematic context. What connected us above all were the martial arts. I come from that world body and soul, and he too trained alongside prominent French karate masters. Those bridges, invisible at first, eventually shaped a common path.

What amuses me today is the parallel between our trajectories. Alan threw himself into cinema with absolute passion, his inner fire, his calling. I spent many years navigating the media world, but always through the lens of martial arts: magazine covers, reports, interviews… Two different roads, yet fueled by the same driving force. And it is undoubtedly this convergence of energy that led us to Lapierre, filmed recently, a project now “in the can,” but above all, a profoundly meaningful human adventure.

Grégoire Canlorbe: Perhaps a word about the character you portray in The Shepherd Code: Lapierre?

David Salucci: In Lapierre, I play a mercenary still in active service, a killer much like Alex Lapierre himself. My character moves in the shadows, in that zone where decisions are made without spectacle, far from the light. He is the one summoned when everything begins to collapse, when a mission drags on, when the boundary between order and chaos grows thin and unstable.

I appear at several pivotal moments in the film with a presence that is discreet, almost spectral, yet undeniably decisive. My character is named Joey “Cobra” Silver, a choice weighted with symbolism. The serpent does not act in turmoil; it watches, waits, then strikes with surgical precision. That is the very essence of Joey, a silent threat, an unpredictable ally, a raw instinct concealed beneath an eerily serene exterior.

Grégoire Canlorbe: Are you satisfied with your performance?

David Salucci: To be completely honest, Lapierre is for me a first immersion, a kind of initiation. My role remains discreet; I appear for perhaps ten minutes in a film that runs just over an hour and twenty. The editing is complete, but the film has not yet been released, so I have only seen a handful of excerpts, fragments, flashes of scenes. And yet, for a first experience, I was genuinely satisfied with the result.

I see this experience as a first step, a way of setting things in motion, of testing my footing in a new world. I needed to feel what it was like, not from the outside but from within: the rhythm, the camera, the silence between takes. And above all, the strange sensation of watching your own performance projected on a screen.

The entire shoot was done in English, which is not insignificant. Even though I speak the language, acting in an idiom that is not your own creates a subtle shift. It is as if you become another version of yourself, one with a slightly different sensibility. Words in a foreign language do not rise from the same place; they impose a distance, a form of restraint. It makes the acting more technical, but also more deliberate.

In the end, I experienced it as an exercise in style, demanding yet profoundly instructive. I know there are a thousand things to refine, but for a first attempt, I believe I managed rather well. What mattered most was having the courage to step through the door.

Grégoire Canlorbe: You studied Claude Goetz’s method in the training of the young Jean-Claude Van Damme: there was even talk, if I am not mistaken, of a book on that subject.

David Salucci: In truth, Goetz is more than an acquaintance; he is a friend. We spent many years in each other’s orbit. I entered his world after writing a biography devoted to Jean-Claude Van Damme, a one-hundred-sixty-five-page manuscript that he himself read and approved. I remained in contact with JCVD for a little over two years. He is a fascinating man, but also extraordinarily complex. What the public sees on television is a softened version. In reality, he is even more intense, more unpredictable. Working with him is a unique experience, at times exhilarating, and at times exhausting. He is a man difficult to contain, a free spirit, elusive and mercurial.

Even before that period, I was already passionate about the biomechanics of the full side split. I began karate in 1986, and I have never stopped practicing. This meticulous work, the technique of the split, the subtle muscular tension—became my true calling card. It was precisely this point of convergence that drew me closer to Claude Goetz, who also attached tremendous importance to that dimension of the body.

I have led countless seminars, trained numerous students, always around stretching, physical preparation, and the pursuit of precise, intelligent movement. It was on this shared ground that our friendship took root. Beyond the tatami, we shared many meals, long conversations, often in the company of his wife, who became very close to mine. The human bond grew naturally from the martial one.

As for JCVD, everything began because Claude dreamed of publishing a book that would reveal him from a different angle, that of the true martial artist. Since I had already authored several works, he entrusted me with the writing. The aim was ambitious: to unveil a lesser-known Van Damme, far from the glitter, more introspective, more authentic. The book was nearly complete: more than two hundred and thirty unpublished photographs waiting to be included, gathered with meticulous care, training sessions, behind-the-scenes moments, suspended instants. JCVD himself had approved them. The project was part archival document, part intimate portrait.

But at the last moment, everything stalled. The family intervened. His mother, his sister… old tensions resurfaced. JCVD found himself caught in the crossfire, torn between loyalty and affection. We chose to pause everything. That familial duality is well-known, an open secret in the milieu. The project ended there, without drama and without resentment. I simply decided not to force fate. Sometimes, one must accept that certain things are meant to remain in the shadows.

Grégoire Canlorbe: A book that seems far closer to a thesis on martial arts, or even psychomotor science, than to a simple biography.

David Salucci: Yes, it was an immense amount of work, ultimately for nothing. Writing a book is an undertaking that devours time, hours of research, cross-checking, interviews. For this one, I was in contact with people who had known JCVD since his youth. It was a plunge into the origins of a myth, but also a craftsman’s labour.

With hindsight, I believe the project belonged more to the realm of the thesis than to that of the biography. It is my natural terrain. I have always had a strong inclination toward philosophy, and the construction of a thesis, with its rigor, its architecture, its demonstration, has become my way of thinking the world. Between 1999 and 2012, I must have written nearly two thousand of them at the federal level. I revisited every advanced kata, re-explained each kick through its intimate mechanics, its muscular insertions, its levers. The aim was to render movement intelligible, to translate into words the invisible logic of the martial gesture.

I also undertook to rewrite traditional karate, to reorganise it, to purify it of what time had eroded. It is fundamental work, almost a quest. I write constantly, sometimes for myself, often for others.

But I harbour no regret. In this milieu, that is simply how things are. In return, other doors opened, other opportunities emerged. I am not ungrateful, I simply acknowledge the customs of a world in which everyone strives to exist.

When you rise in any field, whether sport, cinema, or business, you quickly understand that merit alone is not enough. You must work, certainly, but also strategise, because positions are few and fiercely contested. Some will not hesitate to step on you, to abandon what I call the fundamentals. To survive at that level, you must be armed, technically, mentally, morally. Without that, you do not last.

Grégoire Canlorbe: In a way, you crossed to the other side of the mirror, into the reality of show business beyond the glitter and the bling.

David Salucci: On paper, show business makes you dream, it is a world of light, of promises, of brilliance. But once you step through the mirror, the reality is entirely different. Since 2007, I have moved among what I call the stars up close, that gilded circle which shines from afar yet, seen from within, has nothing celestial about it. I spent many years in that environment, surrounded by actors and public figures, evenings, appearances, smiles, photographs, and behind it all, an immense void.

Because this milieu, despite its seductive veneer, runs on a machinery of pretence. People greet you with open arms, shower you with promises, assure you of wonders, and then, nothing. When the curtain falls, only your work and your integrity remain. In that world, true help never comes from those you expect; it is almost never an actor or a star who opens a door for you. It is sometimes a stranger, an unexpected encounter, a look that believes in you, a gesture offered without interest, rare, almost anachronistic.

Today, the world has sunk into a vortex where values dissolve. Ethics, loyalty, a given word, all of that seems to belong to another age. People have traded integrity for opportunism. And for someone like me, shaped in a world where a word was a vow, the shock is violent.

In the 1980s, in the dojos I knew, there were no borders, no differences. We were two hundred and fifty per club, from every origin, every colour. No one looked at another with suspicion. We trained together, we fell together, we rose together. If someone needed help, everyone rushed in. It was a time when fraternity was not a slogan but a practice, when friendship carried weight and nobility.

Today, everything has fractured. You are judged, classified, labelled. People betray each other for a trivial advantage, for a moment of attention. Some would sell their loyalty for the promise of immediacy. It is a moral ugliness that revolts me, because it denies what makes a man worthy, constancy, integrity, a hand extended when needed.

I have also seen this world from another angle, the vantage point of close protection. I have accompanied important individuals, sometimes in delicate situations, and those experiences opened my eyes. They taught me to read faces, to sense intentions behind smiles. Cinema, seen from the outside, is a dream; from the inside, it is an elegant jungle. It fascinates, yet it devours. It is one of the toughest, cruellest worlds, and also one of the most vibrant. A perfect paradox, like light itself, dazzling, yet blinding.

Grégoire Canlorbe: Many are those who will always prefer remaining in denial to giving up the comfort false promises: those who will always choose the illusion of the easy path rather than face the shock of reality.

David Salucci: Many still live with that hope of effortless glory, that stubborn illusion that believing hard enough is all it takes to succeed. Yet there is a fundamental truth: talent cannot be bought. It is forged slowly, in contact with rigor, doubt, and time.

It is the same in martial arts and in everything that gravitates around them. In the past, some would say: I love karate, I’m a green belt, I’m going to do magazines, covers. In theory, everyone has the right to try. But the moment you choose to enter that world, you become a product. And a product, if it is to be visible, must be identifiable. Your image, your physique, your attitude, everything matters. Behind that façade lies a true process of construction.

If you want to appear in magazines, you need substance, something concrete, a real trajectory. Even a black belt is not enough. To appear on a cover, you must justify your presence. When I found myself in DOJO FIGHT Mag, next to figures like Jon Jones, I knew I had to belong there, that I needed something to say, to embody, to defend. At that level, there is no cheating.

With time, you learn not to confuse dreams with mirages. You cannot promise the impossible to everyone. Among novices, illusion still works; you can make them believe they’ve struck gold. But among insiders, it no longer holds. Maturity is understanding that a film, a career, a project, all of it rests on reality. And reality is that everything has a cost.

When you embark on a first project, even with talent, you must stay lucid. This environment is open to all, certainly, but once you enter it, you too become a product. And that product must be coherent. The image you present must match your means, your world, your identity.

If, for instance, you want to shoot a futuristic movie, a hostage situation in a spaceship with zero budget, you will inevitably fall into kitsch. The final result will never hold up. It is far wiser to build a solid story, human and embodied, without special effects, but with depth, tension, and truth. A clever script, even a modest one, will always have more impact than a blockbuster fantasy without resources.

That is the most common mistake: trying to compete with Hollywood with an empty bank account. Cinema, like life, demands realism. Believing you can build cathedrals out of matchsticks is the surest way to watch everything burn.

Grégoire Canlorbe: How do you present your philosophical treatise and its purpose?

David Salucci: The Philosophical Treatise was not originally conceived as a major work but rather as a booklet, a small, simple format in which I laid down a few essential markers, a kind of philosophical compass meant to recall fundamentals and outline a few paths of reflection. I touched on many themes, without any claim to exhaustiveness; it was intentionally concise, almost stripped down. The format required a certain restraint, it was impossible to delve too deeply without unsettling the balance.

I therefore limited myself to sketching the main lines, the central ideas, without weighing down the writing. It was a first approach, an outline, a way to transmit anchor points to those who, like myself, seek to understand the link between thought and action.

Today, my approach has evolved. With the blog I recently launched, I have found a freer, more dynamic space. There, I develop my reflections without constraint, I expand on the subjects, I dig more deeply into the philosophical roots that underpin the martial gesture. What I appreciate is the possibility of following an idea to its end, of pushing it, of confronting it with reality.

And what is fascinating is that, regardless of the theme I explore, everything eventually converges. Philosophy, discipline, spirituality, martial arts, all obey the same logic, that of the closing circle, the perpetual movement in which every reflection, every experience, leads back to the essential: self-knowledge.

Grégoire Canlorbe: A chapter of your treatise is dedicated to platonic love. How do you summarize your analysis on that topic?

David Salucci: When I revisit the notion of platonic love today, I do so in the light of my own journey. Nothing replaces experience, it alone shapes and refines our certainties. With time, you realise that your stance shifts, that maturity is this slow transition toward the choices that truly matter, especially in love.

In this realm, I believe one should attach oneself only to what is real. Everything else is illusion. When two people meet, man, woman, it makes no difference, everything almost always begins with the physical, a raw, instinctive, animal attraction. We let ourselves be captured by the form while forgetting the substance. But sooner or later, you understand that the body, however perfect, cannot sustain anything over the long term. If there is no soul behind it, no conversation, no depth, beauty crumbles and the bond empties of meaning.

You can walk beside the most beautiful woman in the neighbourhood, feel the glances turning, enjoy the social flattery, but in the end, beauty alone does not hold. If she has nothing to offer beyond her reflection, you eventually lose yourself in it. Love is not a trophy, nor a display window, it is a daily construction, an endurance carried by two.

This is why I distrust purely fantasised love, the kind that exists only on the surface of an image. Everything that is overdone or artificial eventually cracks. In life as in love, you must build on something solid, not on glitter. The person who shares your existence must become your refuge, your mirror, your truth. When you are fortunate enough to meet that person, the one who understands you, helps you, accompanies you without conditions, love takes on another dimension, it becomes sacred.

Look at the world of celebrities, how many parade partners chosen for appearance, for the façade? It is a perpetual performance. Take Schwarzenegger, for example. He embodied absolute success, the body, the cinema, power, glory. His wife came from the Kennedy family, beautiful, tall, brilliant, almost aristocratic. Yet his most sincere love story, his most authentic one, he lived with a woman entirely different, an employee, Mexican, simple, slightly round, with whom he had a child. She was the one who, without knowing it, resembled him the most.

That example says everything. Even at the summit, surrounded by spotlights and pretence, humans end up seeking what is real. You can lie to yourself for a time, display success, play the role of perfection, but you never deceive your own heart. What you run from always catches up with you. And often, it is in simplicity that you rediscover what you had lost, the truth of love, the kind that does not show itself but is lived.

Grégoire Canlorbe: How do you assess Plato’s remark that “the art of gymnastics” pertains to “the body,” and “the art of music,” for its part, to “the soul”?

David Salucci: It is fundamentally true, and even more true than true.

When we reread the great philosophers, we have to picture what they truly were, men seated face to face, in silence, capable of conversing for hours, far from the modern noise, far from screens, notifications, the constant distractions that today erode our attention. They were whole minds, beings who had turned reflection into a way of life. Some quite literally signed their lives with their ideas, to the point of becoming universal landmarks, torches in the history of humanity.

So yes, criticising Plato today would be an absurd form of recklessness. These men were giants of thought, craftsmen of truth, builders of ideas. They had neither the tools nor the technological means we possess, but they had what we have lost, inner availability.

Look around you, minds scatter, consciousness frays. Few people read anymore, few linger over a deep analysis. Information is consumed rather than assimilated. People no longer seek to understand, only to appear. The world has grown accustomed to ease, to the comfort of intellectual laziness, and this drift saddens me.

I no longer recognise myself in it. This world no longer resembles me. My finest years are behind me, and I say it without bitterness. I had the immense privilege of living ten lives in one, of knowing passion, sweat, loyalty, the slowness of things done well. Today everything moves too fast. Young people no longer take the time to live, they scroll through their existence the way one flips through an advertisement.

In the past, seduction came through words, through a glance, through a handwritten letter. One took the time to choose each phrase, to place a feeling on paper, to wait for the reply. There was in all that a gentle gravity, a modesty, a depth. Today everything is instantaneous and therefore everything is replaceable. Perhaps that is the greatest tragedy of our age, having confused speed with life.

Grégoire Canlorbe: The virtual world, while it can help meaningful interactions and meetings to happen, has also erected a barrier between individuals.

David Salucci: We have been completely desocialised, and it was no accident. It was intended, planned, orchestrated. And they have executed it perfectly.

Step into any waiting room and you will see it instantly: no glances, no words. Twenty people seated side by side, each locked inside a digital bubble. Perhaps a timid “hello,” torn from the politeness of another era, but nothing more. Faces have closed, gazes have dimmed. Humanity has dissolved into distraction.

Everywhere, the spectacle is identical. On a terrace under the sun, no one contemplates the horizon, no one savours the moment. People sit motionless, eyes fixed on their phones, scrolling through lives that are not their own. We no longer speak, we no longer listen, we no longer observe.

It is not only sad, it is tragic. Because behind this illusion of connection, there is no true bond. We have traded the warmth of voices for the coldness of screens. And this collective silence, this vast modern muteness, is perhaps the greatest victory of emptiness over speech.

Grégoire Canlorbe: Another remark by Plato to which I believe it is worth returning: submitting oneself to “gymnastics” and “regimens” is a way to intensify “moral ardor,” and not merely “physical strength.”

David Salucci: It is undeniable that training with regularity and intensity elevates you, physically of course, but above all inwardly.

When you truly commit yourself, with a clear objective, almost an existential one, you begin a metamorphosis. You change skin, change gaze, change nature. The person I was at seventeen could never have imagined the man I would become. Everything was built through will, discipline, work, and resilience. Nothing came by chance, I shaped myself, quite literally, through sweat and effort.

The stronger your mind becomes, the more you rise above ambient comfort. Someone who sits across from you without ever having faced effort, without having tasted rigor or the solitude of pushing beyond one’s limits, cannot understand. Courage is not a gift, it is a conquest.

I remember the 2010 kickboxing world championships. I would go running at night, in the suburbs, around two in the morning. Hood pulled tight over my head, “karate contact” sweater on my back, I slipped into the empty streets. I was even stopped by the police once or twice, puzzled to see someone running at that hour. What they could not imagine was that this run was not just training, it was a ritual, a way of forging my mind, hardening myself, reaching for the version of me that did not yet exist.

Very few people know what it is to run alone, in the cold, through silent neighbourhoods, under weary streetlights. Those are the moments that carve your mind, that make you into someone different. Elevation never springs from comfort, it is born from friction with difficulty, from the confrontation with pain.

Because life does not wait for you. You can train, give everything you have, but you must also manage your work, your family, your responsibilities. It is within that constant tension between all the things you carry that true strength is forged.

And by repeatedly stepping out of your comfort zone, voluntarily placing yourself in danger, crossing fatigue and doubt, something within you sharpens. You become more solid, more lucid, more grounded. In the end, what remains is not the performance, but the being. And it is that being, forged in night and sweat, who keeps moving forward when everything else collapses.

Grégoire Canlorbe: There is a difference between being and playing at being: confusion on this point is characteristic of children and of those who refuse to grow up.

David Salucci: Let me tell you something, the one who pretends to be tough never lasts. In life as elsewhere, you cannot cheat for long. When you invent a persona, when you try to make others believe you are someone you are not, sooner or later reality catches up with you.

Social media, at the beginning, had meaning. It was a window into who you truly were, a way to share your work, to pass on experience, perhaps to inspire. When I opened my Facebook account, my intention was simple: to spread a martial message, a philosophy of life, a certain vision of discipline.

Today, all of that has been corrupted. The game has taken over.

In 2004, in Lorraine, I was the first fitness coach. At the time, the very word “coach” made people smile; it was an American term, unfamiliar here. I trained dozens of people over eighteen years, people from all walks of life, lawyers, entrepreneurs, athletes from every horizon. If it lasted that long, it was because the work was real, because the results were there.

Then the word became fashionable. Coaching became a label, a consumer product. Everyone proclaimed themselves a fitness coach without background, without training, without experience. Zero expertise, zero legitimacy, but an Instagram account and a retouched photo. And today the same drift is happening in the world of cinema: everyone is an actor, a stuntman, a screenwriter. Nothing is checked anymore, nothing is validated.

On platforms like YouTube or Facebook, anyone can invent a career, give themselves titles, list achievements, without anyone verifying anything. It has become alarming. The line between truth and illusion has vanished.

As for me, everything I say is traceable, verifiable. I have eighteen federal certifications, each with its official registration number. I am 3rd dan in contact karate with the FFKDA, 6th dan Shotokan with the UNVS, these are facts, not marketing tricks.

What disturbs me is not other people’s success, it is the imposture that has become the norm. The fact that people can fabricate a past, award themselves titles, and everyone simply accepts it. We have normalised deceit. And when falsehood becomes the rule, when legitimacy no longer counts, we condemn an entire generation to illusion.

Grégoire Canlorbe: Thank you for your time. How would you describe the respective ways in which Asia and Europe approach the body and the martial arts, particularly karate?

David Salucci: Today, I condemn a Europe that has profoundly forgotten where karate comes from. Its roots are above all traditional, spiritual, almost sacred. When I began, we drew kihon lines across entire halls. We repeated, again and again, until the movement became truth. It was a pure karate, rough, demanding, a martial art in its strictest sense.

In the 1980s, karate was hard, at times brutal. Knockouts were allowed, gi jackets often ended stained with red. But it was a school of life. You emerged stronger, more dignified. You learned to shape yourself through pain, respect, and the search for balance. It was an art in the deepest sense of the word, a discipline that forged men before producing athletes.

Today, karate has been européanisé. It has become a sport, a spectacle, a showcase. And that saddens me. Karate was never designed to flatter crowds, but to elevate the spirit. It has lost its philosophical dimension, its nobility, its essence. The body still moves, but the soul has grown silent.

That is why many masters, like Roland Habersetzer, chose to step aside, to turn away from the noise of sport-karate and return to the original path, the path of tradition, silence, and inner quest. And I understand them. Because that return is a return to the source, to the truth of movement and of heart.

For me, modern karate has faded, weakened, emptied of meaning. It has turned into a product, when it was once a school of life. And perhaps that is the greatest struggle of our era, to learn again to be martial before being visible, to become true before being seen.

“What I have learned over the years is that you do not triumph by seeking the light, but by learning to walk in the shadows without ever betraying your own path.”

That conversation was originally published on BulletProof Action, in November 2025