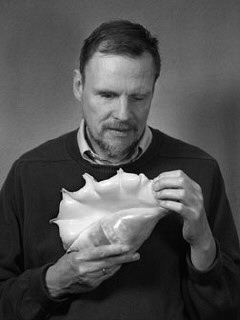

Geerat J. Vermeij is a Dutch-born professor of geology at the University of California at Davis. Blind from the age of three, he graduated from Princeton University in 1968 and received his Ph.D. in biology and geology from Yale University in 1971.

Geerat J. Vermeij is a Dutch-born professor of geology at the University of California at Davis. Blind from the age of three, he graduated from Princeton University in 1968 and received his Ph.D. in biology and geology from Yale University in 1971.

An evolutionary biologist and paleontologist, he studies marine mollusks both as fossils and as living creatures. He started writing about his Escalation hypothesis in the 1970s. He received a MacArthur Fellowship in 1992. In 2000 Vermeij was awarded the Daniel Giraud Elliot Medal from the National Academy of Sciences.

His books include Evolution and Escalation: An Ecological History of Life, A Natural History of Shells, Privileged Hands, Nature: An Economic History, and The Evolutionary World: How Adaptation Explains Everything from Seashells to Civilization.

Grégoire Canlorbe: According to a predominant view in philosophy and in the social sciences, the social hierarchy is an ad hoc cultural construction and not a biological trait. Man is born equal in terms of wealth as well as in terms of social status. Nature spawns neither poor people nor rich people, neither servants nor masters, neither workers nor bosses. Hierarchical relationships are merely cultural, added onto our biological nature (rather than innate). Is this popular view founded, at least in part, in your opinion?

Geerat J. Vermeij: It is true that the human hierarchy is cultural, but there is a substantial cultural inheritance. Although one’s origins can be overcome, the cultural heritability of phenomena such as poverty and status is nonetheless strong, reinforced by epigenetic effects.

Inequality and imperfection, however, appear to be universal and necessary accompaniments to life itself. Whenever organisms interact, one party will almost always gain more or lose less than the other as they compete or cooperate. Very rarely will the outcomes be identical for the participants. Although their fortunes may reverse in the long run, with the underdog persisting longer and ultimately gaining the upper hand, the short-term advantage during interactions tends to belong to the party with the greater power and reach.

This principle applies, for example, to the evolutionary relationship between predator and prey. As a rule, predators exert more intense selection on their prey than prey do on their attackers. Not only do they often kill their victims, but they restrict the times and places in which vulnerable prey can be active. Prey species become important as agents of selection on their attackers only if they are dangerous. Poisonous snakes, stinging wasps, biting crabs, and kicking moose can inflict significant injury on a would-be predator, and could therefore influence the predator’s behavior. Mobbing—large numbers of relatively innocuous prey ganging up on an attacker, as happens when songbirds mount a group defense against a hawk— may also diminish the evolutionary advantage that predators hold over their prey.

Inequalities abound at every scale of biological organization. Ecosystems in which plants and plankton fix carbon by means of photosynthesis subsidize ecosystems that run entirely on food sources derived from photosynthesis. Life on the great abyssal plain of the deep sea depends completely on the steady rain of dead organisms and their excrement falling from the sunlit waters above. It is in the top few hundred meters of the ocean where there is sufficient light for phytoplankton— single-celled life-forms capable of harvesting light and taking up dissolved minerals for photosynthesis— to produce most of the food on which all other living things in the ocean rely. Over the course of evolution, this nutritional subsidy has extended to a subsidy of lineages. The sunlit zone has been the source of most deep-sea groups of organisms, whereas the deep sea has contributed only a handful of cave-dwelling and polar species to the shallow-water ecosystems of the ocean. Land life on the desert shores of Peru, southwestern Africa, and northwestern Mexico is subsidized by marine life in the productive waters just offshore, because seabirds feeding on fish ferry food and feces to shore. Elsewhere, life in the sea benefits from nutrients coming in from rivers that drain rich ecosystems on land. In each of these cases, the more productive system subsidizes, and therefore has a disproportionate influence on, the less productive one.

Even the most egalitarian human societies exhibit inequalities in income and status among individuals, among tribes, among institutions, and among nation-states. Insofar as the price of goods and services is determined by adequate information about supply and demand, producers and merchants possess more information about, and have greater control over, commodities than do individual consumers. Through advertising, they can manipulate demand; and by tracking patterns of what goods and services are sold when, where, and to whom, well-organized companies can predict demand and adjust supply accordingly. Companies simply possess and create a better hypothesis about supply and demand than individuals do, and therefore prices are set largely by them. Their information is, of course, far from complete and may even be inaccurate, but the power it bestows nonetheless remains chiefly in the hands of well-organized enterprises. Only when consumers or labor unions themselves become organized into powerful counterweights to business is this economic inequality lessened or reversed.

The important point is that inequalities arising from differences in access to information or power are not just manifestations of human nature, but pervade the whole of the living world.

Grégoire Canlorbe: In his book Darwin’s Dangerous Idea, Daniel Dennett refers to evolutionary principles as “universal acid” in order to emphasize their all-encompassing explanatory power. According to you, one might equally employ the same metaphor to express the power and reach of the economic perspective, which you see as fundamentally identical to the evolutionary worldview.

Could you explicit and develop this iconoclast point of view? Why do living beings necessarily evolve in an economic world of trade, competition, opportunities and challenges?

Geerat J. Vermeij: Like humans, other living things inevitably compete for (and cooperate to gain access to) locally scarce resources. Competition and resource cooperation are fundamentally economic phenomena. In evolution, survival and reproduction require sufficient resources; therefore, natural selection among phenotypes is fundamentally also an economic phenomenon.

In his book Darwin’s Dangerous Idea, the American philosopher Daniel Dennett indeed characterizes evolution as “universal acid” to emphasize the power of evolutionary thinking to penetrate very nook of human knowledge. But this is a grim image, a metaphor that calls to mind the satanic power feared by doubters and deniers. Evolution is not some corrosive agent, but a universal elixir that enriches those willing to taste it.

Understanding its mechanisms and consequences yields an emotionally satisfying, aesthetically pleasing, and deeply meaningful worldview in which the human condition is bathed in a new light.

[Read more…] about A conversation with Geerat J. Vermeij, for Man and the Economy