Here I intend not only to return to topics such as essence, apodicticity, and the impossibility to deduce material existence from concept—but to address and (positively) evaluate Giovanni Pico della Mirandola’s take on the “dignity of man.” Let us start with reminding the reader that, in my approach to God, the latter is an infinite field of ideational singular models (with generic and unique properties) for singular entities (with generic and unique properties), which finds itself in presence of a (strictly) vertical time (i.e., in which past, present, and future are (strictly) simultaneous); and which finds itself unified, encompassed, traversed, and driven by a sorting, actualizing pulse that is itself ideational and which (in a strictly atemporal mode, i.e., in presence of a strictly vertical time) selects which ideational singular models are to see their correspondent hypothetical material entities being materialized at which point of the universe. While the operation of that pulse is strictly ideational and strictly atemporal, the universe in which the ideational field incarnates itself is strictly material and strictly temporal (i.e., in presence of a strictly horizontal time, in which past, present, and future are successive rather than simultaneous). While incarnating itself wholly into the material, temporal realm, the one of the universe, God remains wholly ideational, atemporal—and wholly external to the material, temporal realm. While endeavoring to engender increasingly higher order and complexity in the universe, God is capable of mistakes in that task—mistakes which man is expected to repair in complete submission to the order that God established within the universe. Also, the atemporal operation of the sorting, actualizing pulse is completely improvisational, what leaves the universe without any predecided, prefixed direction.

The dignity of man

The Mirandolian affirmation that the “dignity of man,” in essence, consists of his finding himself constrained and able to become what he freely decides to become, “like a statuary who receives the charge and the honor of sculpting [his] own person,” is not to be taken in the sense that the human being is a strictly formless, quality-less, matter who can become absolutely whatever pleases him. It is not to be understood either as the negation of the objectively beneficial or harmful character (for the accomplishment of the human being as a human) of certain things and actions. In the Mirandolian conception of the human, the latter, instead of being completely formless, quality-less, is so only to the extent that he finds himself torn between the beast and the divine. Instead of his freedom being that of becoming absolutely whatever he wishes to become, it boils down to the one to “regress towards lower beings in becoming a brute, or to rise in accessing higher, divine things.” Instead of nothing being objectively good or bad for the fulfillment of the human as a human, certain things and actions—including temperance, the golden mean, free mind, obedience to the divine law, knowledge of the cosmic order, white magic, or literary, artistic creation—elevate him towards humanity (and thus towards a so-called “divine” character in the sense of the character of being like-divine, of being made in the image of the divine); others are degrading and change (or maintain) him into a beast, separating him altogether from his virtual humanity. One cannot but notice the similitude with what is part of Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche’s message when he says of the human being that he is “a rope stretched between the beast and the superman;” and that such is what makes him “great.” The conception of the human according to Pico della Mirandola, that of a tightrope walker between the beast and the human-as-divine, is not less similar to what will be the one according to Konrad Zacharias Lorenz and Robert Ardrey when they say of the human, in essence, that he is free to give in to the chaotic, suffocating voice of his instincts or to impose a creative discipline on himself with the help of civilization and of knowledge.

The Mirandolian approach to the human, in which the human’s “nature” lies in its “intermediate position” between the beast and the human-as-divine, and in which the human accomplishes himself, notably, through exerting, developing his ability to think in an independent, critical mode, has nothing to do with Sartrian “existentialism,” in which the human’s “nature” lies in its absence of the slightest “nature;” and in which, nonetheless, the human accomplishes himself, notably, through complete servitude (including intellectual) in an economically communist society. It has nothing to do either with Heideggerian “existentialism,” in which the human’s “nature” notably lies in a virtual role as “shepherd of the Being” that is (according to Heidegger) as much foreign to the crowning of the cosmos through knowledge or through technique as incompatible with any high level of technical development; and in which the human is called to accomplish himself, not as the “lord of the beings” (either in a cognitive sense or in the sense of technical mastery), but as the one who muses over the mystery of the presence of those things that are. The human’s self-accomplishment does not occur through technique stricto sensu in the Mirandolian approach to the human (which, indeed, doesn’t really address the topic of technique—to my knowledge); but it genuinely occurs, for instance, through mastery over nature in a cognitive sense (i.e., through that kind of mastery over nature that is the knowledge of nature), while said mastery is thought in Martin Heidegger to bring absolutely nothing to the human’s self-accomplishment. In the Heideggerian approach to the human, the latter indeed occurs, notably, through meditating over the mystery that there is “something rather than nothing;” but neither through crowning the beings with knowledge nor through crowning them with high technique, which Heidegger even envisions as indissociable from the “forgetfulness of the Being.” The Being is here not to be taken in the sense of an uncreated entity that can neither escape existence (in the general sense of being) nor escape existence in an eternal mode; but in the sense of what allows for existence in existent entities (whether they’re material entities, i.e., materially existent entities) without being itself an entity. The article will resort itself to that definition when speaking of the “Being.” How the Being is actually articulated with the sorting, actualizing ideational pulse is a topic I intend to address elsewhere; but, in that the ideational realm incarnates itself into the material realm (to which it however remains external), the presence of the Being as a background for the ideational realm incarnates itself into the presence of the Being as a background for the material realm (while remaining external to its presence as a background for the material realm). While a property is what is characteristic of an existent or hypothetical entity at some point (whether time is horizontal or vertical), a quality is a property of a non-existential kind, i.e., a property unrelated to the entity’s existence.

A certain modality of the theory of evolution has this negative characteristic (for the spiritual elevation of the human) that it reduces the challenges of the human existence, either individual or collective, to sexual reproduction (and the transmission of genes), thus evacuating the challenge for the individual that is the preparation of oneself for the life of the soul after the death of the body. Another negative characteristic at the level of spiritual elevation is that the modality in question reduces nature to an axiologically neutral battlefield: a land that confronts us with fierce, ruthless physical struggle for the transmission of genes (either individual or collective); but which, remaining rigorously indifferent to human existence and suffering, no more assigns to humans some end to pursue, some model of life to endorse, than it mourns their earthly misfortunes or rejoices in it. Is accordingly evacuated the classic axiological ideal of the pursuit—both at the group and individual level—of a life of moderation in accordance with what is allegedly nature’s expectations: the ideal of the pursuit of the golden mean both in the individual exercise of the mental and bodily faculties—and in the group’s organization and conduct. A golden mean that nature allegedly assigns to us, the transgression of which is allegedly at the origin of most of our earthly ills. The ideal offered in return is that of savagery and excessiveness in the “struggle for survival” and for reproduction, whether it is those of the individual or of the group: Arthur Keith noting in that regard that the “German Führer” was actually an “evolutionist,” who strove to render “the practices of Germany conform to the theory of evolution.” That said, not any modality of the theory of evolution is actually incompatible with the classic ethics of the golden mean—in that a modality (rightly) envisioning the group’s axiological valorization, expectation, of the pursuit of the golden mean both on the individual’s part (in his individual life) and on the group’s part (in its conduct and organization) as an inescapable ingredient to the group’s success in intergroup competition for survival is actually at work, to some extent, in the considerations of “eminent evolutionists” such as Ardrey and Lorenz. The obvious failure of Nazi Germany in the collective struggle for survival is a testimony to the degree to which a group’s imperilment expands as the group deviates from the golden mean. As for the issue of knowing whether the idea of the universe as an axiologically positioned place, i.e., one ascribing us some duties (and some proscriptions), is incompatible with any possible modality of the theory of evolution, I believe my approach to God allows to think of the universe as a place both completely positioned axiologically and—as claimed in the theory of evolution—completely neutral axiologically.

In my approach, indeed, the universe is, on the one hand, completely neutral axiologically in its existence considered independently of the spiritual realm incarnating itself completely into the universe; on the other hand, completely positioned axiologically in its existence considered as an incarnation of the spiritual realm remaining completely external to the universe. What the universe (when considered as a divine incarnation) is axiologically about is, notably, creation; and the fulfillment of creation through the human being, notably, as the latter is made “in the image of God.” It is worth specifying that human creation (in an intellective, mental sense) occurs as much, for instance, at the level of cognition (in a broad sense covering as much art and literature as physics, mathematics, philosophy, magic, etc.) as at the level of technique; just like it is worth specifying that human creation is never so great as when it occurs in the mode of an exploit. What is here called “exploit” is a successful deed that is both exceptionally original, creative, and exceptionally risky, jeopardizing (for one’s individual material subsistence), and which is intended to bring eternal individual glory to its individual perpetrator, whether the exploit occurs on the properly military battlefield or on the battlefield between poets, the one between entrepreneurs, the one between magicians, etc. Properly understood heroism is not about readiness to die anonymously for something “greater than oneself;” but about readiness, instead, to self-singularize and self-immortalize oneself through holding an eternally remembered life of exploit despising comfort and the fear of death. Though Pico della Mirandola rightly conceives of cognitive creation (and independence) and of the golden mean as both constitutive of the human kind’s elevation, thus reminding his reader of those ancient aphorisms that are “Nothing too much,” which “duly prescribes a measure and rule for all the virtues through the concept of the “Mean” of which moral philosophy treats,” and “Know thyself,” which “invites and exhorts us to the [independent, creative] study of the whole nature of which the nature of man is the connecting link and the “mixed potion”,” he didn’t make it clear, sadly, that the human life is never so creative, independent mentally, never so held in accordance with the golden mean, as when it is a life of exploit. It should be added that, when it comes to the pursuit of exploit (especially in the warlike, political fields), a man’s mental creativeness, independence, his inner equilibrium, self-discipline, are never so great as in the one who, quoting Macchiavelli, knows “how to avail himself of the beast and the man” depending on the circumstances, something that “has been figuratively taught to princes by ancient writers, who describe how Achilles and many other princes of old were given to the Centaur Chiron to nurse, who brought them up in his discipline.” To put it in another way, when it comes to war and political fight, a man is never so distanced from the beast that stands at the other end of the rope towards the superhuman as when he finds himself oscillating between the beast and the man with complete flexibility and self-mastery; a point that is regrettably absent in the Mirandolian Oration on the Dignity of Man (but, fortunately, explicit in Niccolò di Bernardo dei Machiavelli’s The Prince).

Again, Nietzsche’s message doesn’t fail to present some similitude with Florentine thinking when (in his Posthumous Fragments) he says that “at each growth of man in greatness and in elevation, he does not fail to grow downwards and towards the monster.” Whether one speaks of “transhumanism” in the notion’s general sense (i.e., in the sense of the promotion of the human being’s “overcoming” through genetic, bio-robotic engineerings), the one I will refer to in the present article (unless specified otherwise), or in the specific sense of an “overcoming” through genetic, bio-robotic engineerings that is specifically intended to emasculate the human being instinctually and mentally, the transhumanist project is obviously incompatible with the Mirandolian, Machiavellian approaches to the human (just like it is with the Nietzschean approach—on another note). Both Pico della Mirandola and Machiavelli (but also Nietzsche) were fully attached to an ethics of exploit with which transhumanism is fully incompatible (a fortiori in the case of the above-evoked specific modality of transhumanism, which I especially addressed in a previous article); just like both (though not Nietzsche) were fully aware that the human was God-established as a worthy master of the cosmos himself put under God’s aegis, an intermediary rank that transhumanism fiercely rejects in its rebellion against the cosmic order. Though the human is God-mandated to crown the beings with knowledge and technique, he is also God-mandated to perform his creativity in the respect of the God-implemented order and laws in the cosmos; in other words, God-mandated to accept himself as being “made in the image of God” (rather than made divine stricto sensu) and to act accordingly. None of the God-implemented laws in the cosmos can be actually transgressed; but attempt to transgress them is, for its part, not only possible but an actual cause of many misfortunes for the human. A plane or bird can no more afford to disdain gravity (if it is to fly) than a human society (if it is to be functional) can afford to dismiss, for instance, the law of the inescapability of genetic inequality in any sexually reproducing species; the law of the instrumental necessity in any vertebrate species of “equal opportunity” for the purpose of the group’s success (in intergroup competition for survival); the law of the impossibility of (rational) central economic-planning; the law of the impossibility of (rational) central eugenics-planning; the law that what can be measured in intelligence is only part of intelligence; the law of the impossibility for the human mind to progress in knowledge (or in any field) without making use of an independent, creative mode of thinking (which is neither measured by the “QI” nor measurable); the law of the impossibility for the human mind (as it has been made by—and positioned within—the cosmos) to do any correct, precise prediction on the consequences of genome-editing; the law of the impossibility for the human mind to gather all the information required for the purpose of eugenics planning (or semi-planning) or economic planning (or semi-planning); the law of the unavoidable perverse-effects of any state-eugenics measure of a coercive, negative, or engineering kind; the law of the impossibility for the human being to master nature (to the extent possible) without submitting himself to nature; the law of the impossibility for the human being’s suprasensible grasp not to be approximative at best; or the law of the impossibility for the human being to reach some knowledge of the cosmos (or of the ideational realm) other than conjectural.

It cannot be denied that transhumanism and the afore-addressed modality of the “theory of evolution”—along with other memetic edifices of the so-called Modernity such as Marxism, Keynesianism, Heideggerianism, or Auguste Comte’s “positivism”—are part of the spiteful ideological mutations that got involved in the human’s corruption over the course of the three last centuries. Almost no longer any “positivist” dares, admittedly, to support or take seriously the notion dear to the earliest positivists, from the time of Auguste Comte, that “science,” far from requesting the slightest imagination, boils down to conducting observations (of regular causal relations) and to inducing them within theories constructed in accordance with “the” laws of formal logic; and that science provides objective certainties instead of being actually conjectural and corroborated. The other articles of the original positivist creed—just as illusory—nevertheless remain deeply engraved in contemporary “neo-positivists.” Just as the so-called positivist spirit represents to itself that nothing exists but what is knowable (under the guise of claiming to restrict itself to knowing what is within the reach of human knowledge), it represents to itself that nothing is knowable but what is completely observable and completely quantifiable, entirely subject to a perfect and necessary regularity (at least, when identical circumstances are repeated over time) and to the identity, non-contradiction, and exclusion of the third middle (at least, in a certain respect at a certain moment). In that, “positivism” is not only unsuited to the (irremediably conjectural) knowledge of the human being, a creature subject (to a certain point) to free will, in whom everything by far is not quantifiable (or completely quantifiable); it is just as much to the (not less irremediably conjectural) knowledge of atomic and subatomic creatures, which, while behaving in a completely quantifiable mode, nonetheless remain free from the exclusion of the third middle (as highlighted by Stéphane Lupasco), perhaps even subject to their own free will to some extent (if one believes Freeman Dyson, Stuart Kauffman, John Conway, Simon Kochen, or Howard Bloom). Positivism is equally mistaken in its conception of science as an undertaking systemically distinct from metaphysics—and in its conception of science as the key to a total human mastery with regard to nature and to an infinite liberation of his creative and exploitative powers. Just as those theories in astrophysics which relate to the beginning of the universe (including the theory of the “Big Bang”) actually tackle, in that, the issue of the “first causes,” the interest that “science” has in the allegedly necessary regularities in the causal relations between material entities (in a broad sense including atoms), what is commonly called “laws of nature,” is never more than a modality of the interest in “essences” which occupies a part of ontology. To say of material entities that they follow a perfectly necessary regularity in all or part of their causal relations which is inherent in what they are actually falls within the discourse on “essences.” As for the mastery over the universe that science is able to bring to man, it is no more total than science is able to provide objectively certain theories. Far from science being able to render the human a god, it can only render him “as master and possessor” of nature: render him as-divine within the limits assigned to science and to the human by the order inherent in the cosmos, an order to which human submission is necessary condition for the liberation (to the extent possible) of his own creative and exploitative powers.

A scientific statement is never objectively certain nor a strict description of the sensible datum; but is instead a conjectured, corroborated statement. Precisely, what defines a scientific statement is not its object—but the fact it is conjectured, corroborated, and the way it is conjectured, corroborated (namely that is panoramically conjectured, corroborated). A claim or concept is conjectured when it is guessed from something which objectively doesn’t prove it. A claim or concept conjectured at an empirical level (what is tantamount to saying: a claim or concept conjectured in an empirical sense) means a claim or concept conjectured from sensible experience; just like a claim or concept conjectured in a panoramic sense (what is tantamount to saying: a claim or concept conjectured at a panoramic level) means a claim or concept conjectured as much from sensible experience as from some logical laws as from hypothetical sensible impression (i.e., from sensible impression perhaps) as from hypothetical suprasensible impression (i.e., from suprasensible impression perhaps) as from hypothetical conjectures from sensible experience as from hypothetical ones from sensible impression (i.e., from ones perhaps from sensible impression) as from hypothetical ones from suprasensible impression as from hypothetical ones from hypothetical other conjectures from sensible experience, hypothetical other ones from some logical laws, hypothetical other ones from suprasensible impression, and hypothetical other ones from sensible impression, whether those hypothetical other conjectures are one’s conjectures or borrowed to someone else. A claim or concept is corroborated when it is backed in a way that (objectively) doesn’t confirm it nonetheless. Corroboration at an empirical level (what is tantamount to saying: corroboration in an empirical sense) for a concept or claim means its corroboration through sensible experience; just like corroboration in a panoramic sense (what is tantamount to saying: corroboration at a panoramic level) for a concept or claim means its corroboration as much through sensible experience as through some logical laws as through hypothetical sensible impression (i.e., through sensible impression perhaps) as through hypothetical suprasensible impression (i.e., through suprasensible impression perhaps) as through hypothetical conjectures from sensible experience as through hypothetical ones from sensible impression (i.e., through ones perhaps from sensible impression) as through hypothetical ones from suprasensible impression as through hypothetical ones from hypothetical other conjectures from sensible experience, hypothetical other ones from some logical laws, hypothetical other ones from suprasensible impression, and hypothetical other ones from sensible impression, whether those hypothetical other conjectures are one’s conjectures or borrowed to someone else.

The logical laws used, trusted, in one’s mind are completely interdependent with the universe such as empirically conjectured in one’s mind or represented in one’s sensible impression, such as represented in one’s hypothetical suprasensible impression, such as conjectured from one’s logical laws, and such as represented in one’s hypothetical conjecturing from one’s sensible experience, in one’s hypothetical conjecturing from one’s (hypothetical) sensible impressions, in one’s hypothetical conjecturing from one’s (hypothetical) suprasensible impressions, and in one’s hypothetical conjecturing from hypothetical other conjectures from sensible experience and from hypothetical other ones from suprasensible impression and from hypothetical other ones from sensible impression (whether those hypothetical other conjectures are one’s conjectures or borrowed to someone else). The scientific claims and concepts (what is tantamount to saying: the scientific theories and concepts) sometimes think of themselves as being conjectured only from the sensible datum and corroborated only from the latter; but they’re actually claims and concepts panoramically conjectured (including from the sensible datum) and panoramically corroborated (including from the sensible datum). As for the metaphysical claims and concepts, they’re neither systemically conjectured in a panoramic mode nor systemically corroborated in a panoramic mode; but, when they’re empirically corroborated, they’re also panoramically corroborated (and panoramically conjectured). Any scientific claim or concept is panoramically conjectured, corroborated; but not any panoramically conjectured, corroborated, claim or concept is scientific. A scientific claim or concept is a modality of a panoramically conjectured, corroborated, claim or concept that not only allows for not-trivial quantitative positive predictions expected to be repeatedly verified under the repetition of some specific circumstances; but sees itself doomed to get empirically disproved in the hypothetical case where all or part of those predictions would be empirically refuted at some point.

From white and black magic to white and black technique

Technique is here taken in the sense of any apparatus intended to increase the human’s transformative or exploitive powers—whether it is through extending, sophisticating the social division of labor or through devising, deploying new technologies or through organizing society in a certain way aimed at increasing said powers. Most opponents to technique claim that they have something only against preferring technique over meditation on the Being, i.e., meditation on the mystery of the existence of things; or that they have something only against after preferring technique over the moderation of sensitive, material appetites, or over “heroism” understood as the capacity to die for one’s community or for something greater than oneself. Precisely, an error on their part lies in their more or less implicit assertion that a high level of technical development (i.e., a high level of development in all or part of the aforementioned modalities of technique) is necessarily incompatible with the meditation on the Being, the mastery of the sensitive, material appetites, or the sense of self-sacrifice—as if there were a choice to do between high technique (i.e., high technical development) and one or the other of those things. Another error on their part lies in their more or less explicit approach to Being, the glade of existence, as a closed, complete glade, which only asks the human to meditate on the fact that there is something rather than nothing, that there is a glade rather than the night. Actually, the Being is open, incomplete, waiting for the human to pursue what exists prior to the human and to make himself the brush-cutter and arranger of the glade. Technique is no more external to the opening of the human to the Being than a high level of technical development necessarily breaks said opening. Heidegger simply failed to notice that the technique opens us as much to the Being as does meditation of the fact of existence; and that the human fulfills his role of “shepherd of the Being” as much in the astonished consideration of the presence of things as in the cognitive, technical completion of the present things. Meditative astonishment at the mystery of existence is not doomed to disappear as knowledge and technique are boarding (and prolonging) what exists; but its vocation in “the history of the Being” is to stand at the side of technical development as asked by the Being itself.

Two things, at least, should be clarified. Namely that, on the one hand, the axiological, organizational hegemony of the market (which can only be majorly at work, not completely) doesn’t lead to the axiological, organizational promotion (either complete or major) of intemperance in society; and that, on the other hand, not all technique is good technic from the joint angle of the Being, of the divine order, and of the “human dignity.” (What is bad technique from the angle of the Being is also bad technique from those two other angles. Ditto for what is bad technique from the angle of the divine order—and bad technique from the angle of the “human dignity.”) A society that is strictly industrious in its foundations, i.e., where the industrious activity (instead of the military one) is the dominant activity in the organization and the foundational code of expectations, is not systemically a society that notably values, expects, intemperance and which articulates its industrious activity around it notably. Such society is instead a modality of the industrious society. With regard to the modality where the market is largely liberated and largely hegemonic at the organizational and axiological levels, that hegemony of a largely liberated market not only does not imply that a complete or high intemperance is valued in the foundational expectations or put at the core of social organization; but, besides, is simply incompatible with such an organizational or axiological hegemony of intemperance. A largely liberated market notably requires (as would be the case of a perfectly liberated market) for its proper functioning the presence of (quantitatively) numerous and profitable outlets, what notably requires the presence of a virtuous circle where high levels of savings obtained notably through high or perfect temperance create—notably through a correct entrepreneurial anticipation of the respective consumption and investment demands—high levels of entrepreneurial and capital income, themselves reinjected in part into savings and in part into consumption. The modality of an industrious society where the market is largely hegemonic at organizational and axiological levels (in other words, the modality of an industrious society that is the majorly bourgeois society) is therefore a modality whose code of expectations condemns the slightest intemperance (instead of encouraging or tolerating it) and whose organization is based on high or full temperance (rather than high or moderate intemperance). What one may call the Keynesian modality of an industrious society, where the economic system is largely based on economic policy measures whose interference with the market intentionally encourages high levels of consumption (to the detriment of levels of savings which be high or moderate), is actually a modality that axiologically praises high intemperance notably and which notably relies on it in the organization; but that modality, precisely, is neither one where the market is majorly (or completely) liberated nor one where it is majorly (or completely) hegemonic in values.

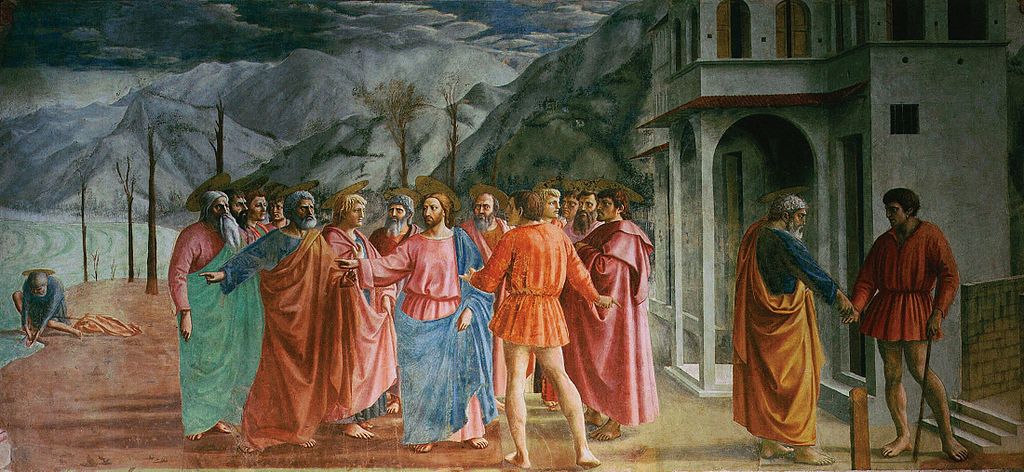

It is true that a society where the market is majorly hegemonic (both organizationally and axiologically) is a society where the valued, expected code of conduct in the foundations of said society includes—apart from self-sacrifice on the battlefield in intergroup warfare—concern for pursuing as a priority, placing above all else, a perfectly temperate and perfectly responsible subsistence, which be so long as possible and which avoid danger as much as possible; but intemperance, whether high, complete, low, or moderate, is just as incompatible with such code of conduct as (strictly) high or complete temperance is indispensable to the organization of a society where a largely liberated market is largely hegemonic. Just as the bourgeois code of conduct and indulgence with regard to such-or-such level of intemperance (were it the lowest) are wholly distinct (and even wholly incompatible) things, a (completely) Keynesian market and a widely liberated market are wholly distinct (and even wholly incompatible) things. Just as a largely liberated and largely hegemonic (axiologically and organizationally) market requires quantitatively numerous and profitable outlets for its proper functioning, it requires qualitatively numerous and profitable outlets: in other words, profitable outlets that are “diverse and varied” (rather than homogeneous). It is not only false that a largely liberated and largely hegemonic (axiologically and organizationally) market requires for its proper functioning a (strictly) complete or high intemperance; it is just as much false that a largely liberated and largely hegemonic (axiologically and organizationally) market requires standardized outlets for its proper functioning. Whatever the level of liberalization of the national or global market, a double cause-and-effect relationship that is at work both in the national and global market is effectively the following. Namely that the more the profitable outlets are qualitatively numerous (i.e., diversified at the level of their respective attributes), the more they are quantitatively numerous; the less they are qualitatively numerous, the less they are quantitatively numerous. The highly standardized character of goods and services in the contemporary global market is precisely a dysfunctional pattern in the globalized market; and that dysfunctional motive is itself the consequence of the fact that, however globalized it may be, the globalized market is largely hampered juridically—and hampered for the benefit of a narrow number of companies and banks enjoying fiscal and legal advantages that are such that those companies and banks are largely sheltered from competition. Both at the national-market level and at the global-market level: the more competition is juridically locked, the less the profitable outlets are qualitatively, quantitatively numerous; the less it is, the more they are. Just like a society that majorly prefers technique over exploit, i.e., which majorly disdains exploit for the benefit of technique, is majorly detrimental to the human’s elevation towards the superhuman, a society that completely prefers technique over exploit (as is the case of a majorly bourgeois society—and as would be the case of a completely bourgeois chimerical society) is completely detrimental to the human’s elevation towards the superhuman. Technique is not more to be preferred (completely or majorly) over exploit than the latter is to be preferred (completely or majorly) over the former. Both are compatible and should go hand in hand (as is the case in some modalities of a society completely warlike foundationally). Yet the opponents to technique err not only in their amalgamating disdain for heroism with disdain for temperance; but in their understanding heroism as a conduct incompatible with (high) technique—and as a conduct turned towards self-erasure and self-sacrifice through anonymous death (even while heroism is really about self-singularization and self-immortalization through exploit such as defined above). What’s more, they fail to notice that the problem with technique is not only to be aware not to prefer technique over that to which it should remain not-preferred; but to be aware not to indulge into what can be called black technique or bad technique (in comparison with that kind of magic that can be called black or bad). Precisely, the distinction that Pico della Mirandola takes up (and clarifies) between two kinds of magic, the one which “entirely falls within the action and authority of demons” and the one which instead consists of “the perfect fulfillment of natural philosophy,” must extend to technique. Namely that, while the good, white technique is the one which is only the crowning of the natural order, the completion of the Being, the bad, black technique is the one which (were it unwittingly) works to transgress the natural order, subvert the Being. The former contributes to fulfilling the human as a being-as-divine, but the latter, working (were it unwittingly) to render the human divine, contributes to corrupting him and handing him over to the demons. The former really institutes the human as a fortunate co-creator alongside the divine, but the latter, indulging in the chimerical project of escaping the cosmic order and equaling the divine, only makes to condemn the human and his work to misfortune. Just as bad magic, to quote Pico, is, rightly, “condemned and cursed not only by the Christian religion [of the type of Catholicism of Pico’s time], but by all laws, by every well ordered state,” the bad technique must be legally, politically, religiously condemned unambiguously. The transhumanist, so to speak, must be led to the stake just like the Keynesian. From engineering on the genome of embryos to those neuro-robotic implants undermining free will, from genetic planning to any coercive, negative, or engineering state-eugenics measure, from economic planning to any economic-policy measure undermining such things as inheritance, free competition, saving, or the freedom itself to do saving, demonic-type technique must be banned in its entirety; but good technique, the one which elevates us towards God and the superhuman, must be authorized.

That first part was originally published in The Postil Magazine’s November 2021 issue.

Causality, necessity, and permanence

Existence at some point in material entities is both endowed with an originated character (i.e., the character of finding its origin somewhere—whether the entity is created rather than uncreated); and with the character of being either permanent (i.e., doomed to continue) or provisory (i.e., doomed to end). Also, material entities (such as the human intellect represents them to itself in its impressions or in its conjectures, if not from sensible experience, at least from what it thinks to be sensible experience taken as such, i.e., naked, mere sensible experience) are engaged in causal relations; what is tantamount to saying that they’re endowed with causal relational properties. Though some men are able to have suprasensible access (to the ideational realm), their access is irremediably made, strictly, of “impressions” (i.e., illusions produced by suprasensible experience), which are approximately true at best. As for the human intellect’s contact with sensible experience, it is (strictly) made of observations and of impressions (i.e., illusions produced by sensible experience, which look like sensible experience but are instead deformed echoes of what is actually observed). Yet Hume’s assertion, in essence, that the concept of (efficient) cause in the human intellect is the strict account of the impression of a sequence necessarily repeated identically that is only produced in it by the regular sensible experience of a chain repeating itself identically (under identical circumstances) is false on at least two levels. On the one hand, that affirmation confuses the concept of (efficient) cause and the concept of an efficient cause whose effect is not only necessary at time t but necessarily identical to itself over the course of time. On the other hand, it is mistaken about the relation of the human intellect to sensible experience, which it wrongly conceives of as a strict relation of observation and impression by habit. One thing is to say that the impact of the ball with the pool cue is the efficient cause of the movement of the ball at time t, but another is to say that the impact in question necessarily causes the movement in question at the concerned time. Yet another is to say that, if, in the future, the shock is repeated strictly identically under strictly identical circumstances, then the effect itself will necessarily repeat itself each time (and, each time, will necessarily repeat identically); regardless of the time the shock identically repeats under identical circumstances. As for the relation of the ontological concepts of the human intellect (including the efficient cause—and the efficient cause jointly necessary and necessarily identical to itself under identical circumstances over time) to sensible experience, it is most likely that each ontological concept taken in isolation, whatever it may be, finds its complete origin, either in one or more human instincts, or in conjectures of the human intellect in contact with (naked) sensible experience, or in one or more sensible impressions (i.e., one or more impressions produced by the sensible experience on the human intellect), or in conjectures of the human intellect in contact with one or more sensible impressions, or in a legacy of the acquired culture, or in one or more suprasensible impressions, or in a mixture between all or part of those things.

Whatever its origin, the human intellect opts for trusting an ontological concept in its possession if (and only if) it judges the latter as being confirmed by the sensible (and hypothetically suprasensible) experience or judges it as being (highly) corroborated by the sensible (and hypothetically suprasensible) experience or judges it as being (highly) corroborated in the panoramic sense. Even if the concept of (efficient) cause were actually the strict fruit of the account of a certain (sensible) impression made on the human mind, the presence of that concept in the human intellect cannot have as a necessary condition the account of the (sensible) impression made on the human intellect by the specific mode of chaining that is a chain of events repeating itself identically under identical circumstances; because any observed sequence making an impression on the human intellect, whether the sequence in question is repeated (and whether it is identically repeated under identical circumstances), would then be capable of producing the impression of the action of an efficient cause. But, although sensible experience is only able to corroborate our ontological concepts and the suprasensible is only made of impressions, the relation of the human mind to the latter is actually active (and not only passive, i.e., not only made of observations and impressions). Our intellect is active towards them in that it assesses them and relies on them. Whether the human intellect confuses sensible impression with sensible experience when thinking some ontological concept (for instance, the concept of efficient cause) to be (highly) corroborated by sensible experience changes nothing to the fact that it then thinks the ontological concept in question to be (highly) corroborated by sensible experience; just like the fact that it confuses sensible impression with sensible experience when thinking some ontological concept (for instance, the concept of efficient cause) to be confirmed by sensible experience changes nothing to the fact that it then thinks the ontological concept in question to be confirmed by sensible experience. Yet the human intellect doesn’t only endorse this or that ontological concept according to whether it thinks or not the latter to be empirically confirmed or (either empirically or panoramically) corroborated; it also tries to articulate them with each other in the way that makes most sense in view of each other, in view of sensible experience, and in view of corroboration in a panoramic sense.I intend to show (a few lines later) that those causal relational properties that are identically repeated when identical circumstances are repeated make most sense when understood as constitutive properties that are, besides, correspondent to intrinsically necessary dispositions that—in addition to their presence at the “substantial” level in the entity—apply to any moment witnessing the presence of some circumstances. I cannot say more about it for now.

Just like those causal relational properties identically repeated (when identical circumstances are repeated) are part of the constitutive properties of a (singular) material entity endowed with such properties, they’re part of the constitutive properties of a generic material entity endowed with such properties. Therefore they as much belong, so to speak, to the adequate definition for the concept whose object is the singular entity in question as they belong, so to speak, to the concept whose object is the generic entity in question. The “eye of the world” that is the human (not in the sense that he is a way for the universe of seeing, knowing, the universe—either correctly or approximately—but in the sense that he is able, mandated, to approach exact knowledge of the universe without ever reaching it) is notably able (and mandated) to approach exact knowledge of the material essences in material entities without ever reaching said knowledge. (Approximative) knowledge of the “laws of nature” is, precisely, part of the (approximative) wider knowledge of “material essences.” What a “material essence” exactly means in the article is the set of the constitutive properties in a material entity (which—as I intend to develop a few lines later—are not all “natural” properties and are not all “substantial” properties). Grasping perfectly (or almost perfectly) a material essence in a material entity amounts to obtaining a perfect (or almost perfect) definition of the concept for the material entity in question. When a material entity is rendered the object of a concept, the concept in question always means, indeed, the entity in question strictly taken from the angle of its constitutive properties, i.e., strictly taken from the angle of its material essence. As for the definition socially correspondent (in some language) to a concept whose object is a material entity, it exposes what the language in question thinks are the constitutive properties of the material entity in question. Hence the concept in question and its socially correspondent definition are held as synonyms in the language en question. Part of the cognitive process leading to move closer to perfect knowledge of a material essence consists of selecting some socially admitted definitions and questioning their validity. It is worth specifying that pseudo-definitions must be distinguished from actual definitions. While the latter only deal with constitutive properties (and with the totality of the constitutive properties), the former deal with any kind of property. Also, while the latter notably include ones socially admitted, which, in some language, are attached to correspondent concepts and accordingly held to be synonymous with the concepts in question, the former are of strictly private use. Just like the fact that some language deems some definition to be true (i.e., to expose adequately the totality of the constitutive properties in the correspondent concept’s object) doesn’t render the definition in question true, the fact that some language deems two terms or a term and a sequence of terms (when taken in a certain conceptual acceptation) to be synonymous (i.e., endowed with equivalent senses) doesn’t render them true synonyms. While a concept (strictly) means its object taken from the angle of its constitutive properties (setting aside for now the case of those concepts with meaning-modalities), its definition (strictly) exposes what the definition in question claims are the constitutive properties in the concept’s object.

Whether a concept deals with a singular entity (either material or ideational), a genre (either material or ideational), or a property (either material or ideational), its socially admitted definition (in some language) is socially deemed to be synonymous with its meaning, i.e., with its object taken from the angle of its constitutive properties. For instance, if some language defines the genre duck as “a waterbird with a broad blunt bill, short legs, webbed feet, and a waddling gait,” then the term “duck” (when taken in the right conceptual acceptation) and sequence “a waterbird with a broad blunt bill, short legs, webbed feet, and a waddling gait” will be held as synonymous in the language in question. In other words, the concept duck’s meaning (i.e., the object referred to as duck taken from the angle of its constitutive properties) will be deemed to be synonymous with the meaning of the above-evoked sequence. Just like any concept for a genre (whether it deals with a genre of ideational singular entities or a genre of material singular entities) deals with some of the generic properties of some singular entity, any concept for a singular entity (whether it deals with an ideational singular entity or a material singular entity) deals with the whole of the constitutive properties in its object. The set of those generic properties in a singular entity (whether it is material or ideational) that are constitutive is only part of the constitutive properties; but, while the constitutive properties are only part of the properties in a material singular entity, all properties in an ideational singular entity are constitutive properties. Just like any material entity is a singular (rather than generic) entity, any ideational entity is a singular (rather than generic) entity. Also, just like any entity (whether it is material or ideational) falls within some genres, the expression “generic entity” is only a convenient way of designating a genre to which some entity (either material or ideational) happens to belong. For instance, the singular material entity that is a singular duck belongs to the “generic material entity” that is the genre duck; and the singular ideational entity that is the singular Idea for some singular duck belongs to the “generic ideational entity” that is the generic Idea for the genre duck. In both cases, the genre in question—instead of being an entity strictly speaking—is only a set of constitutive properties. Also, in both cases, those generic properties that are constitutive are only part of the constitutive properties; but, while the constitutive properties of a singular material duck are themselves only part of the duck’s properties, all properties in the singular ideational model for the singular material duck in question are constitutive properties. A concept for an alleged singular entity (whether it is material or ideational) always deals (only) with the set of the constitutive properties in its objet; but, while a concept for an ideational singular entity deals with all properties in its object (as all properties in its object are constitutive), a concept for a material singular entity deals with only some part of the properties in its object. The hypothetical entity modeled in an ideational entity must be distinguished from the ideational entity. Here I won’t deal with what are the properties in an ideational singular entity apart from those related to how it designs the hypothetically materialized entity modeled within it.

All properties in a genre or in a property are constitutive, not all properties in a singular entity; but here I will leave aside the case of those concepts dealing with a property (apart from noting that those concepts also deal with their respective object taken from the angle of its constitutive properties). Just like a same word can subsume several concepts (for instance, the word “duck”), a same concept can subsume several meanings—namely a general meaning and its several modalities (paradoxically including the general meaning itself taken in isolation). For instance, the concept of color includes a general meaning for which the socially admitted correspondent definition is “a visual characteristic distinct from those visual characteristics that are the size, the shape, the thickness, and the transparency;” and subaltern, specific meanings—including one for which the socially admitted correspondent definition is “a visual characteristic that, besides being distinct from those other visual characteristics that are the size, the shape, the thickness, and the transparency, finds itself associated with a wavelength.” If correctly constructed (what is tantamount to saying: if correctly defined), a concept for some material entity (or for some generic material entity) endowed with only one meaning is then perfectly mirroring the modeled constitutive properties inscribed in the ideational essence of its object (without the ideational essence containing only those properties in the modeled entity that are constitutive); just like, if correctly constructed (what is tantamount to saying: if correctly defined), a same concept for several material entities (or several generic material entities) endowed with a general meaning and some modalities for the latter is then perfectly mirroring the modeled constitutive properties inscribed in the respective ideational essence for the respective object of each of its meaning-modalities (without the respective ideational essences containing only those properties in the respective modeled entities that are constitutive). Just like a good definition generally speaking (i.e., a good definition as much in the case of ideational as in the one of material objects, as much in the case of generic objects as in the one of singular objects, as much in the case of entities-objects as in the case of properties-objects, and as much in the case of real objects as in the case of unreal objects) strictly deals with the correspondent concept’s object taken from the angle of its constitutive properties (or with the constitutive properties of one of the correspondent concept’s objects), the set of the constitutive properties in a (singular) material entity form what may be called its material essence.

Yet a proper presentation of the way the essence in any material entity is subdivided into four distinct essences (namely the ideational essence, the material essence, the natural essence, and the substantial essence) requires preliminary partial presentation of the subdivision between the several kinds of property totally or partly present in any entity (whether ideational or material)—and of the subdivision between the several kinds of origin and of permanence (or provisority) for existence in an existent entity (whether ideational or material). The properties in an individual entity (at some point) are notably classified as follows. 1) Constitutive properties vs. accessory properties. 2) Intrinsically necessary properties vs. intrinsically or extrinsically contingent properties. 3) Extrinsically necessary properties vs. intrinsically necessary or extrinsically contingent properties. 4) Unique properties vs. generic properties. 5) Relational properties vs. non-relational properties. 6) Existential properties vs. non-existential properties (i.e., qualities). 7) Fundamental properties vs. secondary properties. 8) Innate properties vs. emergent properties (whether in the general sense of posteriorly appearing properties—or in the precise sense of posteriorly appearing properties bringing about novelty in the world in terms of non-existential characteristics, i.e., in terms of qualities). 9) Permanent properties in an intrinsically necessary mode vs. properties with an extrinsically necessary permanent character or an intrinsically necessary provisory character. 10) Provisory properties in an intrinsically necessary mode vs. properties permanent in an extrinsically or intrinsically necessary mode. 11) Compositional properties (i.e., about what the entity is made of) vs. formal properties (i.e., about how the entity is shaped from its matter). 12) Dispositional properties (i.e., about what the entity would do if put in presence in some circumstances at some moment) vs. concrete properties. As for the modes of origin and permanence (or provisority) for an entity, they’re notably classified as follows. 1) Intrinsically necessary entities versus intrinsically or extrinsically contingent entities. 2) Permanent entities in an intrinsically necessary mode versus entities provisory in an intrinsically necessary mode—or permanent in an extrinsically necessary mode.

An intrinsically necessary property of the strong kind is one that an entity (whether it is material), at some point, cannot but possess independently of what are the entity’s relations at any point of its existence (and independently of whether the entity has relations at any point of its existence); except the entity in question needs to be presently existent (if it is to possess the property in question), what requires some relations at some point before in the case of any entity different from God. An intrinsically necessary property of the weak kind is one that an entity, at some point, cannot but possess independently of what are the entity’s relations at any point of its existence (and independently of whether the entity has relations at any point of its existence); except the entity in question needs to be presently existent and intact (if it is to possess the property in question), what requires some relations at some point before in the case of any entity different from God. Just like the entity’s existence at the present time is a necessary, sufficient cause for any intrinsically necessary property of the strong kind that is then present in the entity, the entity’s existence and integrity at the present time is a necessary, sufficient cause for any intrinsically necessary property of the weak kind that is then present in the entity. An intrinsically necessary property (whether it is of the strong kind) that is dispositional is a modality of an intrinsically necessary property; but not any dispositional property is an intrinsically necessary property. An extrinsically necessary property is one that an entity, at some point, cannot but possess due to the entity’s existence and to the combination, at some point before, between the entity’s existence, an intrinsically necessary property (for instance, a dispositional intrinsically necessary property) in the entity, and one or more relations in which the entity finds itself engaged at that anterior moment. For instance, the property for a point mass, at some point, of exerting an attraction force towards another one that is “proportional to the product of the two masses and inversely proportional to the square of the distance between them” is a relational extrinsically necessary property that is a forced product of the entity’s existence at that point and of the combination (at some point before) between the entity’s existence, another relational property (namely the presence of another point mass somewhere), and a dispositional intrinsically necessary property (namely the property of exerting an attraction force such as described above when another point mass is present somewhere). An intrinsically contingent property is one whose existence, at some point, in an entity finds a necessary, sufficient cause in the fact that the entity’s existence at that point is added to the occurrence, at some point before, of a combination between the entity’s existence, an intrinsically necessary property in the entity, and one or more relations on its part at that anterior moment. Just like any intrinsically contingent property is one extrinsically necessary, any extrinsically necessary property is one intrinsically contingent. An extrinsically contingent property is one that is present at some point in an entity as a random product of the fact that the entity’s existence at that point is added to the occurrence, at some point before, of a combination between the entity’s existence, an intrinsically necessary property, and one or more relations; but which finds in that fact whose random product it is a necessary (though not-sufficient) cause. No relational property (except in the case of God) is one intrinsically necessary; but any relational property (except in the case of God) is either extrinsically contingent or extrinsically necessary. A property that an entity, at some point, possesses because of its present existence and of the combination (at some point before) between an effective free volition on its part, its existence, one ore more relations on its part, and an intrinsically necessary property in it is a modality of an extrinsically contingent property.

Just like a property that is, at some point, permanent is a property that is, at the considered moment, doomed to continue to exist in the entity without any interruption (so long as the entity will keep up being existent), a property that is, at some point, provisory is a property that is, at the considered moment, doomed to cease to exist in the entity, either in a determinate (or more or less determinate) future moment in which the entity will be still existent, or in an indeterminate (or more or less indeterminate) future moment in which the entity will be still existent. An intrinsically necessary property (whether it is of the strong kind) is either permanent or provisory; just like an extrinsically necessary property is either permanent of provisory—and just like an extrinsically contingent property is either permanent or provisory. A permanent property is either permanent in an intrinsically necessary mode or permanent in an extrinsically necessary mode; just like a provisory property is always provisory in an intrinsically necessary mode. A property that, at some point, is permanent in a strong intrinsically necessary mode is a property that, at the moment in question, is doomed to continue to exist in the entity (so long as the latter will keep up existing) independently of what are the entity’s relations at any point of its existence (and independently of whether the entity has relations at any point of its existence); except the entity in question needs to be presently existent (if the property in question is to be presently permanent), what requires some relations at some point before in the case of any entity different from God. A property that, at some point, is permanent in a weak intrinsically necessary mode is a property that, at the moment in question, is doomed to continue to exist in the entity (so long as the latter will keep up existing) independently of what are the entity’s relations at any point of its existence (and independently of whether the entity has relations at any point of its existence); except the entity in question needs to be presently existent and intact (if the property in question is to be presently permanent), what requires some relations at some point before in the case of any entity different from God. Just like the entity’s existence at the present time is a necessary, sufficient cause for the permanence of any property that is presently permanent in a strong intrinsically necessary mode in the entity, the entity’s existence and integrity at the present time is a necessary, sufficient cause for the permanence of any property that is presently permanent in a weak intrinsically necessary mode in the entity. A property that, at some point, is provisory in an intrinsically necessary mode is a property that, at the moment in question, is doomed to cease to exist in the entity (at a future moment—either determinate (or more or less determinate) or indeterminate (or more or less indeterminate)—in which the entity will be still existent) independently of what are the entity’s relations at any point of its existence (and independently of whether the entity has relations at any point of its existence); except the entity in question needs to be presently existent (if the property in question is to be presently provisory), what requires some relations at some point before in the case of any entity different from God. The entity’s existence at the present time is a necessary, sufficient cause for the provisory character of any property that is presently provisory in an intrinsically necessary mode in the entity. A property that, at some point, is permanent in an extrinsically necessary mode is a property that, at the considered moment, is permanent because of the entity’s present existence and because of the combination (at some point before) between the entity’s existence, an intrinsically necessary property in the entity, and one or more relations on its part. Any property permanent in an extrinsically necessary mode is also permanent in an intrinsically contingent mode—namely that those things form a necessary, sufficient set of causes for its permanence.

An intrinsically necessary entity is one that, at some point, cannot but exist independently of what are the other entities in the universe (and in the ideational realm) at any point (and independently of whether other entities are existent at any point in the universe and in the ideational realm). As for an extrinsically necessary entity, it is one that, at some point, cannot but exist due to the combination, at some point before, between another entity’s existence, an intrinsically necessary property in that other entity, and one or more relations in which that other entity finds itself engaged (at that anterior moment). Just like an entity that cannot but exist in an eternal mode (i.e., in a mode devoid of any beginning in time and any ending in time) is a modality of an entity that is intrinsically necessary, an entity that is self-created but cannot escape its self-creation is another modality of an entity that is intrinsically necessary. An intrinsically contingent entity is an entity whose existence at some point finds a necessary, sufficient condition in the fact that a combination occurs, at some point before, between another entity’s existence, an intrinsically necessary property in that other entity, and one or more relations in which that other entity finds itself engaged (at that anterior moment). Just like any intrinsically contingent entity is one extrinsically necessary, any extrinsically necessary entity is one intrinsically contingent. An extrinsically contingent entity is an entity that, at some point, finds itself, either existent because of the entity’s random self-creation from nothing at some point before, or existent because of the entity’s random apparition, at some point before, from a combination happening even earlier between another entity’s existence, an intrinsically necessary property in the latter, and one or more relations on the latter’s part; and whose present existence finds a necessary, sufficient cause in the fact of having been engendered in one or the other of those ways. Just like God is an intrinsically necessary entity in an inescapable eternal mode, the universe is both an extrinsically necessary entity with regard to God—and an extrinsically contingent entity in a randomly self-created mode with regard to the nothingness preceding the universe. No entity apart from the universe can be one, at some point, both extrinsically necessary (from some respect) and extrinsically contingent (from some respect). Just like an entity permanent in an intrinsically necessary mode at some point is an entity that, at the considered moment, is doomed to continue to exist independently of what are the entity’s relations (and independently of whether the entity has relations), an entity provisory in an intrinsically necessary mode at some point is an entity that, at the considered moment, is doomed to cease to exist at a future moment—either determinate (or more or less determinate) or indeterminate (or more or less indeterminate—independently of what are the entity’s relations at any point of its existence (and independently of whether the entity has relations at any point of its existence). As for an entity permanent in an extrinsically necessary (but intrinsically contingent) mode at some point, it is an entity that, at the considered moment, is doomed to continue to exist because of the entity’s present existence and because of the combination (at some point before) between the entity’s existence, an intrinsically necessary property in the entity, and one or more relations on its part; and which finds in the set of those causes a necessary, sufficient set of causes for its permanence.

Just as an existent entity that is permanent at a certain moment is an entity that, at the concerned moment, is doomed to continue to exist without any interruption, an existent property that is permanent in a certain entity at a certain moment is a property that, at the concerned moment, is doomed to continue to exist without any interruption in the entity (so long as said entity will exist). Just as an existent entity that is provisory at a certain moment is an entity that, at the concerned moment, is doomed to cease to exist either at a determinate (or more or less determinate) moment or at an indeterminate (or more or less indeterminate) moment, an existent property that is provisory at a certain moment is a property that, at the concerned moment, is doomed to cease to exist in the entity either at a determinate (or more or less indeterminate) moment in which the entity will still be existent, either at an indeterminate (or more or less indeterminate) moment in which the entity will still be existent. Just as an existent entity, at a certain moment, is, at the considered moment, either existent in an intrinsically necessary mode, or existent in an extrinsically necessary (but intrinsically contingent) mode, or existent in an extrinsically contingent mode, an existent property in a certain entity, at a certain moment, is, at the considered moment, either existent in an intrinsically necessary mode, or existent in an extrinsically necessary (but intrinsically contingent) mode, or existent in an extrinsically contingent mode. Just as an existent entity, at a certain moment, is, at the considered moment, either permanent in an intrinsically necessary mode, or provisory in an intrinsically necessary mode, or permanent in an extrinsically necessary (but intrinsically contingent) mode, an existent property in a certain entity, at a certain moment, is, at the considered moment, either permanent in an intrinsically necessary mode, or provisory in an intrinsically necessary mode, or permanent in an extrinsically necessary (but intrinsically contingent) mode. Rings that, at any time, would render anyone who wears them immortal would provide an extrinsically necessary permanence to the human wearing them on his wrists at a given time; but a machine that provisorily keeps someone alive provides neither any extrinsically necessary permanence nor any permanence at all. The universe is permanent in an extrinsically necessary mode with regard to God; but permanent in an intrinsically necessary mode with respect to the nothingness preceding the universe. No entity other than the universe can be permanent in an extrinsically necessary mode.

In its general sense, “the mode of existence” for an entity here means the set of its existential properties over the course of its existence; but, in its stronger sense, here means the set of those existential properties over the course of its existence that are about the origin for an entity’s existence—plus those about whether and how it is permanent or provisory. Unless specified otherwise, the article will resort to that concept in that stronger sense exclusively. The mode of existence (in the above-evoked strong sense), at some point, for an entity that is, at that point, existent is an existential innate property with strong intrinsic necessity and with strong intrinsically necessary permanence. Yet a material entity is endowed with four essences. Firstly, the ideational essence—namely the sum of all the properties of an entity over the course of its existence. Secondly, the material essence—namely the sum of all the constitutive properties of an entity over the course of its existence. Thirdly, the natural material essence—namely the sum of all those constitutive properties of an entity over the course of its existence that are intrinsically necessary properties, whether of the weak kind or of the strong kind. Fourthly, the substantial natural material essence—namely the sum of all those intrinsically necessary constitutive properties of the strong kind that are both innate and endowed with intrinsically necessary permanence of the strong kind. The mode of existence (i.e., those existential properties about whether and how a material entity is necessary or contingent—and about whether and how it is permanent or provisory) is part of the substantial natural material essence. Just like not any existential property in a material entity is part of the substantial natural material essence, not any substantial natural material property is an existential property; but when a material entity loses all or part of its substantial natural material properties, it always loses its property of existing on that occasion—and reciprocally. In other words, a material entity ceases to exist when (and only when) it loses all or part of its substantial natural material properties. Any substantial property is a constitutive property; but not any constitutive property is a substantial property. Any intrinsically necessary property is a constitutive property; but not any constitutive property is an intrinsically necessary property. Some generic properties are constitutive properties; but not any generic property is a constitutive property. Some generic properties are intrinsically necessary; but not any generic property is intrinsically necessary. The natural material essence in a material entity is the sum of all the intrinsically necessary constitutive properties (whether intrinsically necessary of the strong kind) in the entity—including (but not only) those intrinsically necessary constitutive properties in the entity that are generic.

My quadripartite approach to the essence in a material entity allows solving a number of ontological problems—including (but not only) the problem of how and when an entity ceases to exist. Namely that a material entity ceases to exist when (and only when) it loses all or part of its substantial natural material properties, a loss that always brings about the one of the property of existing (though the latter is no more part of the substantial essence in a perishable—and, accordingly, provisory in an intrinsically necessary mode—entity than is the property of dying). What’s more, my approach to the essence in a material entity allows solving the ontological problem of the universe’s jump from nothingness. If someone has voluntarily put a hat on his head at some point and wears it right now, the property in him of wearing a hat is an extrinsically contingent property that is the random product of his present existence and of an earlier combination between an intrinsically necessary dispositional property (namely the ability to put and wear a hat in the ongoing context), existence, and several relations (including the relational property of finding himself in a place where the wind doesn’t prevent him from wearing a hat). More precisely, it is a modality of an extrinsically contingent property that is an extrinsically contingent property associated with free will—namely the considered human’s free decision to wear a hat. So long as the hat remains pulled down on his head, the hat is then permanent in an extrinsically necessary mode. As for the universe’s birth from nothingness, just like the toothpaste’s gush from the tube at some point is a non-existential extrinsically necessary property in the toothpaste, the universe’s gush from nothingness at some point (namely at the initial instant in our universe) is, with regard to the nothingness chronologically preceding the universe, an extrinsically contingent mode of origin for the universe that is an existential property intrinsically necessary of the strong kind in the universe. More precisely, it is a modality of an extrinsically contingent existence that consists of existing in a randomly self-created mode. Yet the universe is (at any point) endowed with intrinsically necessary permanence of the strong kind with regard to the nothingness preceding it. The universe, when considered with respect to the nothingness chronologically anterior to the universe, is therefore a material entity endowed with the innate, intrinsically necessary (of the strong kind) property of being extrinsically contingent—and of being permanent in a strong intrinsically necessary mode.